Remember Anthony Ant, Musician and Community-Builder, in All His Soaring Glory

The East Bay trumpeter and reverend of the jam scene showed us the true power of music.

The East Bay trumpeter and reverend of the jam scene showed us the true power of music.

This week we've got more Lunar New Year events, kinky emos, and a pozole pop-up.

Easy “go-to” recipes are at the center of Maxine Sharf’s cookbook, with a panoply of healthy dishes inspired by her upbringing in the East Bay.

The East Bay trumpeter and reverend of the jam scene showed us the true power of music.

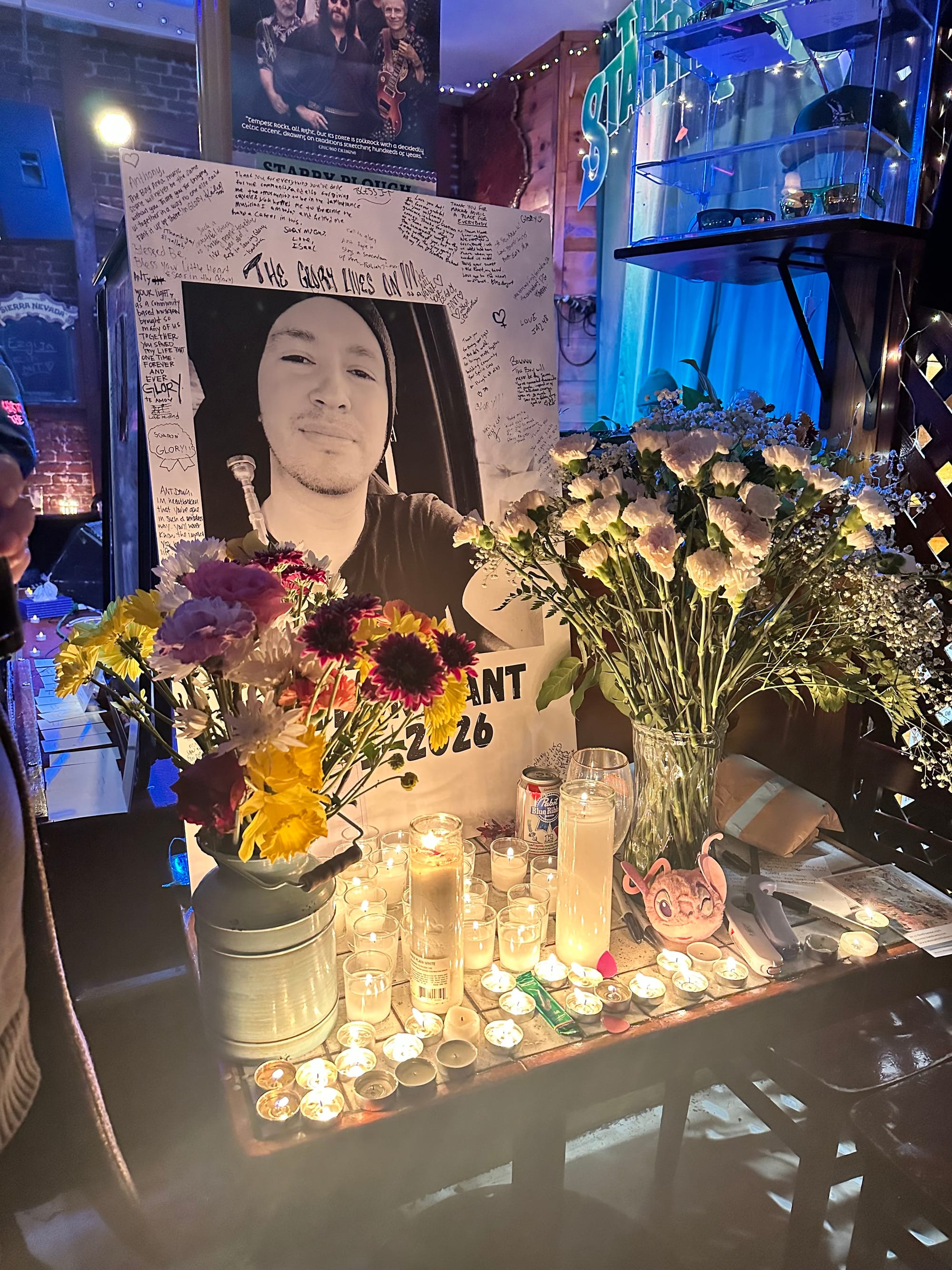

Ed. note: Since Feb. 9, the Bay Area music scene has been reeling from the loss of Anthony Anderson, a trumpet player, show promoter, and tireless community connector who brought people together through live music. While his death at the hands of Alameda County sheriff’s deputies is under investigation, those who knew “Ant” have been mourning and celebrating his life with stories of what the musician, who died at age 40, meant to the community. Here is one such tribute, from drummer Dan Schwartz.

I can’t be sure exactly when I first met Anthony Ant. I think it was at a jam at Berkeley’s Beckett’s, now Tupper and Reed. Either way, it was he who collected me — got my number, hit me up for another jam a few days later. I say that not out of pride, but because that is what he did: He collected people around music.

By early 2012, we were housemates. Together with four or five other people (depending on who was staying on the couch), we lived on the border of Oakland and Berkeley in a duplex dubbed The Church House. It earned this name because in the upstairs unit we would host a Sunday night jam session, whose weekly catharsis offered an almost cultish sense of community for twenty-somethings discovering the seemingly unbridled possibility of Occupy-era Oakland.

It soon became clear that Anthony, dubbed “Reverend Anthony Ant” by some, was the heart of these gatherings — he made it more than a party. Armed with a trumpet and a stash of PBR, Anthony would lead each session to, in his words, Ultimate Soaring Glory, crying out the exultation (“GLORY!”) with which he soon became synonymous after any particularly potent jam. And while there was always a dash of self-mockery in Anthony’s language, the truth was not lost on any of us: The power of music was building community and allowing people to truly let loose, something that feels all too rare at even the best live shows.

To an East Coast transplant like myself, Ant — who grew up in Berkeley — seemed like a genuine, though unassuming, Bay Area freak (in the most endearing sense). He was a night owl, and slept until 4 or 5pm each day with his head wrapped thick in t-shirts to block light and sound. He would allude to his earlier years (as if, at 25, he had already lived many lives) as a long-haired hitch-hiking “traveler kid,” a graffiti writer, and owner of a pet pigeon. He would sit in his car and practice trumpet along to KBLX for hours, retraining himself out of some bad technique he’d picked up along the way. Artists and music lovers of all kinds were drawn to him and his enormous grin. He called people “glorious mofos” while appreciating their quirks. At the end of the night, he would pay musicians by making them hold out their hands and slapping it repeatedly with cash, saying, “Take it! Take your dirty monehs!”

Around the same time that the Church jams were happening, Anthony and his friend Dustin Smithwaite also began hosting a more official jam at The Layover in downtown Oakland. When he first invited me down to play I was nervous, thinking I would be eaten alive by legendary Oakland drummers. It turns out the jam was pretty disorganized, the bar was pretty empty, and it seemed like the few musicians they’d gathered couldn’t settle on a genre.

Fast forward, and by late 2012 he had turned that jam into the most rambunctious, popping Wednesday night in the Bay. Anthony made it happen by texting, for hours, everyone he knew, every week. It worked. Musicians from all corners of the city were showing up. In addition to the typical East Bay R&B and hip-hop representatives, cumbia and Balkan musicians would regularly roll through. A Cuban cohort would play percussion on the sidelines, and the dance floor would sweat. By the end of his first year at The Layover, I remember cumbia bassist Dan Yockey was already saying Anthony would go down in the books of Bay Area music history as a crucial scene-builder. Countless friendships, bands, communities, and relationships had been forged in the fires of “Ultimate Soaring Glory,” and that was only a year or two into the saga.

When the Layover jam ended, I thought, Damn, that’s too bad. End of an era.

Not for Anthony. Instead, he replaced it with two weekly sessions at Era Art Bar and The Starry Plough, and then, eventually at the Legionnaire Saloon, where the levels of musicianship and community only continued to expand and evolve.

It all flourished because Ant had a knack for leading without needing to center himself. His sessions would always feature a vocalist and a set list, but a majority of the material was improvised. He trusted the musicians he invited to be the house band each week, often folks who had never played together or even met each other. There was never any rehearsal. Even Oakadelic, the band he fronted around the Bay and beyond, was essentially a jam session on wheels: deeply improvisational with rarely repeating personnel. While Anthony inhabited the center of a vast musical community, and was often technically the band leader, he did not seek the spotlight. Every event, no matter what it was supposed to be, was a vehicle for musical ascension — and good hangs.

Left: Anderson, middle, with Oakadelic. (Photo by Ant Nef) Right: Anderson speaks at a Decentered Arts studio show. (Photo by Mia Terracotta)

His stage presence was effortless, mostly because he was joyfully and unapologetically himself. Often first-timers were unsure of whether they should be offended or laugh at the things he said as an MC, as he intoned slang like “woot holla woot” and “I’m officially getting my swerve on,” in his distinct nasally white boy drawl after playing some R&B deep cut.

It all worked because he was equal parts self-mocking and completely genuine. At a time when Oakland was (is) being rampantly gentrified and accusations of appropriation were to be avoided at all costs, Anthony never shied away from his own personality. He did piss some people off — I saw it — but no one ever questioned his intentions. His commitment to his own twinkling strangeness brought together a huge and wildly diverse group of musicians, and fostered a space of joyful acceptance in resistance to the encroaching condominiums.

There are many out there who were closer to Anthony than I was, but I feel lucky and thankful to have experienced a long and satisfying musical journey by his side. I doubt there is anyone in the Bay Area who has done as much to bring people together around music, in community and joy. The outpouring of grief and tributes after his death has been astonishing, only because his influence extends beyond what I had even imagined.

In the shadow of his loss, I feel the reminder that the true value of one’s musicianship is displayed not through virtuosity, recordings or fame, but through the power to alchemize a sense of joy, connection, and belonging from presence and sound. This is something Anthony understood and offered night after night — in all his grinning glory.