In Which I Decide to Liquefy My Body After Death

Water cremation, also known as “aquamation,” is gaining traction as an environmentally-friendly alternative to traditional cremation by fire. But what exactly is it?

Water cremation, also known as “aquamation,” is gaining traction as an environmentally-friendly alternative to traditional cremation by fire. But what exactly is it?

The sordid tale of the freelancer who never was.

This week we've got Valentine’s AND anti-Valentine’s parties, vampire drag, and deep dives into Pompeii and ancient Egypt.

Water cremation, also known as “aquamation,” is gaining traction as an environmentally-friendly alternative to traditional cremation by fire. But what exactly is it?

A couple months ago, I took a tour of the East Bay wastewater treatment plant. The huge facility is best known to residents by its smell; there is no avoiding its presence while driving eastbound on the I-580 from San Francisco. It’s where all the water from our toilets, showers, and washing machines go — but that’s not all. As I gazed up at the huge tanks during my visit, half-listening to the tour guide, I heard her casually mention that if you are cremated by water, you, too, can end up being processed at the treatment plant.

I’m sorry, what??

The rest of the tour went by in a blur as I got lost in a Google wormhole. Aquamation — also known as water cremation, flameless cremation, green cremation, biocremation, or chemical cremation — is a not-uncommon way to dispose of a body, it turns out. But the more I researched, the more my questions multiplied. What’s left over after you’re aquamated? Is your liquefied flesh really sent to the water treatment plant? How long does the process take? And, why doesn’t anyone I’ve talked to know aquamation exists?

I turned to the local expert on such things. Frank Rivero is the owner of Emeryville's Pacific Interment, a funeral business that conducts traditional fire cremations, embalming, burials, and, as of 2024, aquamation.

He came to it, he tells me, when he was looking for a more environmentally friendly way to dispose of bodies. “We have a traditional flame crematory,” he says, but “it does put out a fair bit of carbon. We were trying to figure out a way to reduce our footprint, and that’s when we came across aquamation.”

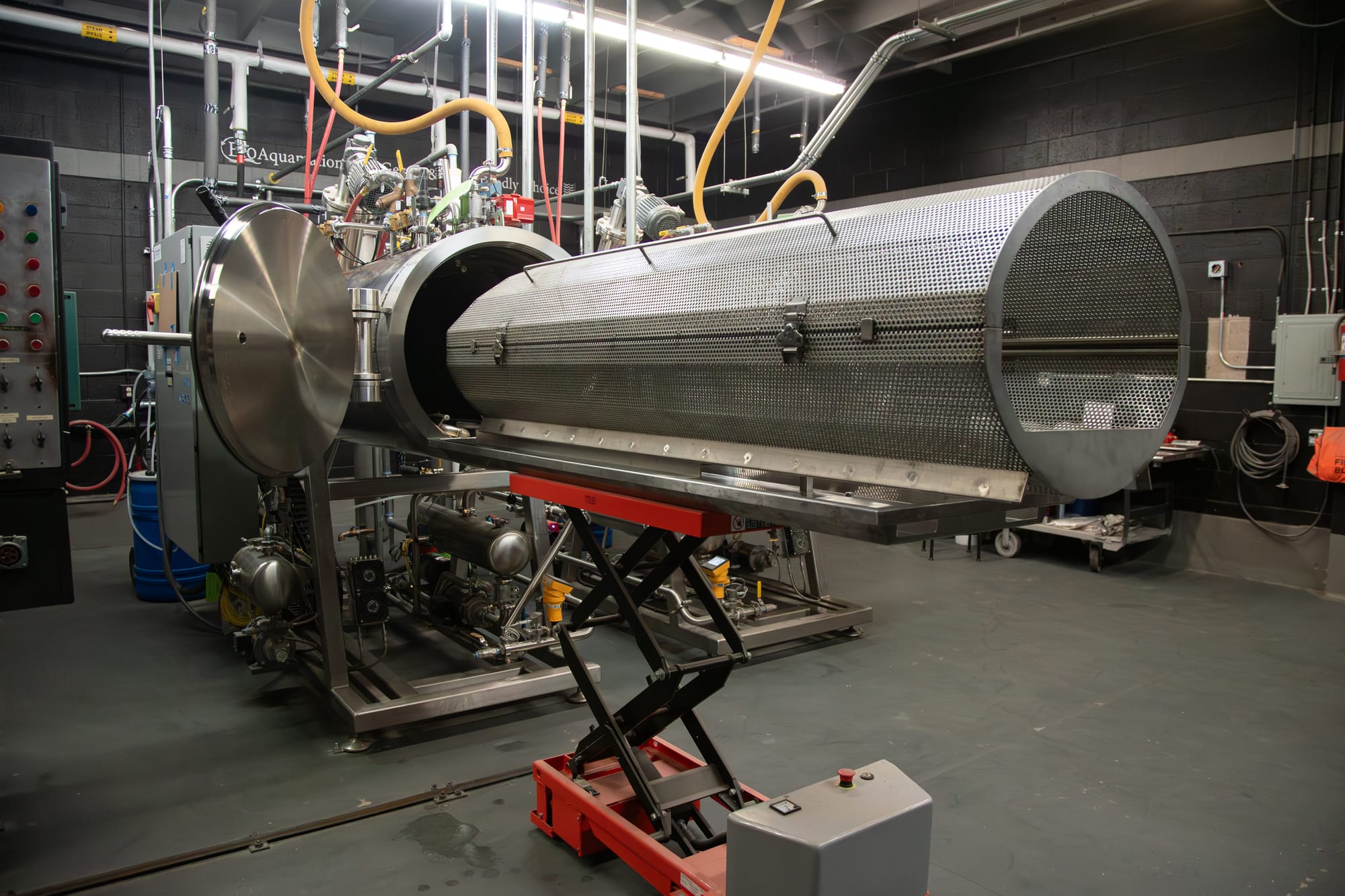

This form of disposal seems futuristic, but it’s surprisingly simple. A body is placed inside a long metal tube, which is then filled with more than 100 gallons of heated water and alkaline chemicals. This decomposes fat and tissue, just like when a body is buried — but in three speedy hours.

Aquamation is not new. It was originally used for processing dead livestock, most notably during the mad cow epidemic in the 1990s, as its end product is totally sterile. It was extended to pets and then started becoming popular for human body disposals across the country. In 2017, California passed AB967, becoming the 15th state to create regulations on aquamation for human remains.

It’s slowly picking up speed. When Desmond Tutu died in 2022, he chose to be aquamated in South Africa, boosting the system’s popularity across the world.

Since Rivero installed an aquamation machine at his Emeryville facility in late 2024, he’s processed around 100 bodies, far fewer than through fire cremation. He’s seeing a shift, however, as more people learn about it.

“Burial comes with a very expensive price tag. In talking to people, it’s often the reluctance to incinerate their loved ones more than any ecological considerations,” he says. “Aquamation is really the middle ground for those who want to have something a little gentler than a cremation. It’s eco-friendly, and they can still have the remains with them.”

The liquid, now called “effluence,” is completely sterile and harmless. Pacific Interment has permits with the East Bay Municipal Utility District to release the effluence into the wastewater system, after undergoing testing twice a year.

“Every test has come up completely benign,” Rivero says. “There’s nothing in that water, even things you would expect. When you go through a lifetime, you could be exposed to chemotherapy agents, radiation, or pharmaceuticals. Those are retained in your body, but the aquamation process completely neutralizes all of that. What comes out is completely harmless to the environment.”

In fact, wastewater treatment engineers love having effluence in their mix. It’s nutrient rich, and helps feed the bacteria that is processing the waste in their tanks.

“Fire cremation results in various air emissions and release of plastic and metals within our bodies,” Andrea Pook, the public information officer with EBMUD, tells me. “In the case of aquamation, mercury fillings, for example, are recovered, rather than released as air emissions; medical device implants can likewise be recovered. The liquid waste, if sent directly to our digesters, would result in significant biogas production.”

Effluence isn’t the only byproduct of aquamation. Inside the tank, what’s left are fragments of very clean white bones (think about what you see washed up on a beach), and as Andrea points out, any metal implants like dental fillings or screws. The bones can then be ground into a fine powder, and given to the decedent's loved ones in an urn, just like ashes — but much cleaner.

(L) Lazaro Rivero points at the screen on the side of an aquamation machine used to enter information about the person inside — such as their weight. (R) Before entering the aquamation machine, bodies are placed into its interior tank. (Amir Aziz/COYOTE Media Collective)

Every time I think about this, the giant from Jack and the Beanstalk enters the chat, discussing how he wants to “grind your bones to make my bread."

Fictional threats aside, “It is a very gentle process,” Rivero says. “It leaves behind a skeleton, basically that’s all calcium, as opposed to the cremated remains. They’re much lighter and whiter than what you get back after traditional cremation.” (To see what they look like, go to 1:30 on this video.)

In researching this process, I became somewhat obsessed, heralding aquamation’s benefits at every opportunity. (Oddly, I learned, people don’t want to hear about how it works over dinner.) It also sent me into an existential tailspin, likely because I never took AP Chemistry and don’t understand the science of it all. If the effluence comes out completely clean, where does one’s flesh and muscle go? How do our bodies simply disappear when we die? What do we become? Does it even matter, if our bodies are just a shell?

I don’t have answers, but I do have a plan for my dead body. I shall be agitated in a metal coffin, blasted with heat and alkaline, and dissolved into nothingness until only my bones remain. Part of me can’t wait.

Nuala Bishari is an investigative journalist and opinion columnist who's reported on the Bay Area since 2013. She writes about public health, homelessness, LGBTQ+ issues, and nature.

View articles