How Racket, Minneapolis’s Worker-Owned Newsroom, Is Covering Its Hometown Fascist Invasion

“This is the worst fucking time. But watching people’s response to ICE has been the most affirming thing in the world.”

“This is the worst fucking time. But watching people’s response to ICE has been the most affirming thing in the world.”

This week we've got strikes, slime, white rappers, psychics, goth nights, and more.

It’s time to stop waiting around for those in power to save us. We, the people, can get everyone’s basic needs met.

Times are tough. ‘Freestyle Mania’ bent them into the shape of a balloon animal for one glorious afternoon.

The first time I tried buying Monster Jam tickets in August, my credit card company shot me down. “Do you recognize this purchase?” an email read. Potential fraudulent activity; suspicious behavior. Fair enough — it was a decidedly uncharacteristic move, on my part, given the circumstances of our political reality. It had thus far been a shit year for those of us long weary of American brawn’s omnipresent symbols: trucks, guns, flags, and the thugs getting paid to wield all three. What I wanted these days, more than anything, was one good night of sleep. Instead, I’d signed up for V8 “Reveille.”

Though Floridian, I do not come from the monster truck region of the state. The town of Palmetto, which idles along a strip of the Manatee River before reaching the Gulf, is home to Monster Jam’s headquarters. I have been there in the way people from Florida have always been there if you ask them about anywhere in Florida (and also never by equal measure). I have been through with the hubris of a Miamian. Until now, I’ve never asked more of the place.

Still, the monster truck commercials of the 1990s loomed large. I can recall TV ads featuring old cars getting crushed or leapt over by the double-neck guitar of motorsports: a massive American truck on 66-inch tires, flag waving from its rear, signaling the promise and threat of unabashed white masculinity. The crowds and their demographics were implied; the absent ones, too.

That was then. These times had brought out the why the fuck not in me like never before. A low-stakes impulsiveness not unlike the one that bloomed across the early days of the pandemic, when 30-year-olds took up sourdough starters and roller skates (my own skateboard still hangs on the wall, its TOMO grip tape of broken hearts neglected, its wheel’s bearings dust-lodged and blue). I wanted to feel the indulgence of cheap awe as an adult, however ridiculous, during a stupendously terrible time in this country. When a billboard near the MacArthur Maze flashed an ad for Monster Jam Freestyle Mania, as I sat wedged in Oakland’s rush hour traffic, I immediately knew I’d found it.

On a gray morning this September, I left my house and walked toward a Coliseum-bound BART train. At 9:30 a.m. on a Saturday, there was little on the platform save for mystery liquids and a smattering of locals. An advertisement on the far side of the tracks implored me to purchase special eyeglasses to stop facial recognition systems in their tracks. By this point, I’d relied on KN95 masks to block half of my face for years, though the Zenni ad suggested I could be doing more. What my myopia lacked, it implied, was sufficient dystopic alarm.

Once inside the train car, I attempt to get myself hyped for monsters through the power of music, but all my saved albums are of the winsome sad boy variety. Jangly guitars but minor keys. An ocean of hi-hats but drowned out lyrics. It’s autumn, I tell myself. An excuse of a truth for a lie.

Stepping out at the Coliseum station, I hit play on a Sharp Pins record. The sky is the color of ashes, my hoodie hunter green, the “fi” appropriately “lo.” I am a cliché of elder millennial tropes in a film directed by too many aughts men to count.

Somehow, it isn’t embarrassment that stops me mid-step but a sudden sense of unease — I’ve never seen the pedestrian bridge linking the train to the Coliseum and Oakland Arena empty and hope never to do so again. The curved borders of its chain-link fence stripped of buskers and vendors hawking A’s merch or grilled meats. It is the unsettling opposite of Nicole Kidman’s AMC ad. It is Tom Cruise running through an empty Times Square in Vanilla Sky, the world apocalyptically devoid of everything and everyone that made this city home to me. The silence is haunting, and I finally feel, if not hyped for monsters exactly, then at least thematically apprehensive.

A security guard at the end of the bridge waves me left. “Monster Jam?” I ask. “Yup,” he nods, glancing only briefly from his folding chair.

Then we are waved again (by this time, a father and son are behind me). And then again by more guards, past the Rickey Henderson Field sign under the aged-gray ‘E’ of the Coliseum. Finally, we reach the South Arena gate.

Though the competition begins at 1pm, the Pit Party — a chance for visitors to see the monster trucks and their drivers up close for an additional $20 — is already underway.

I pause about 30 feet from the entrance gate’s metal detectors to get a sense of the type of person who attends a Monster Jam. A kid, about five years old, runs by me with a checkered racing flag in his hand, decked out in a matching hoodie-and-shorts set repping Grave Digger, Monster Jam’s flagship truck that dates back to 1982 in the form of a mud racing 1951 Ford pickup. His father follows behind him wearing Adidas track pants and a sweater.

Another child walks by in a similarly themed green-and-black pom pom beanie. A mother follows suit. The trickle of reapers grows to a flood. “This is a lot of Grave Digging for 10:30 a.m.,” I scribble into a notebook. Above us, a Dolly Parton billboard instructs folks to “find the good in everybody.” The “PRIVACY IS FOR THE PEOPLE” Mullvad VPN billboard opposite Dolly suggests we think twice about that.

It dawns on me that I am the only person here without children in tow. In fact, I am suspiciously un-childed and have lingered too long, the wary glances from security guards a warning. I don’t blame them — I might as well have arrived early to size up the fans at Disney on Ice (which, not coincidentally, is also produced by Feld Entertainment, purveyors of Monster Jam since 2008). If I’d bothered looking at the Pit Party page, I would have realized what plenty of parents already did: It’s a thin line between Monster Jam and Monsters, Inc.

Despite having lived here for nine years, it is my first time inside the Oakland Arena, the place I should have Valkyries season tickets to but don’t, and about which I remain bitter. By the entrance doors lies a merch table almost exclusively aimed at an age demographic that wasn’t yet born when I first left NYC for California. There are the children’s T-shirts and hats and protective hearing devices for their tiny heads, alongside a selection of Feld-licensed toys and plushie trucks.

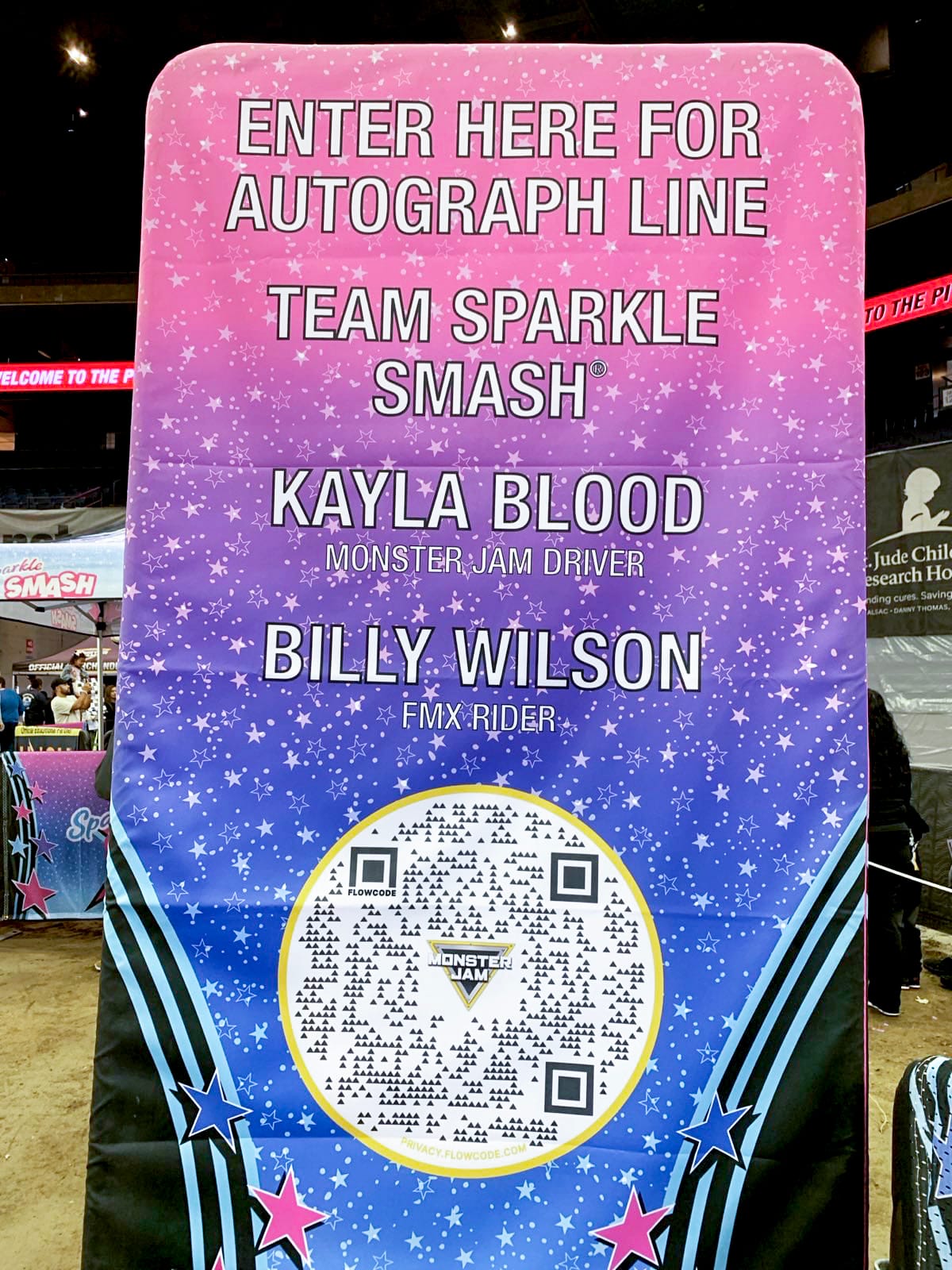

(L) Rahawa standing in front of the Grave Digger monster truck. (R) A sign at the entrance to the Sparkle Smash autograph line. (Rahawa Haile/ COYOTE Media Collective)

As we are all funneled through the lower decks of the arena, a parade of “wows” streams under a large, inflatable arc resembling the top half of a monster truck tire, the inverted triangle of Monster Jam’s logo resting at its crown.

Finally, we have arrived at the dirt track: From end to end, it’s about 100 Rahawa steps. Its perimeter is lined by behemoths. “Each Monster Jam truck is approximately 10.5 feet tall, 12.5 feet wide, 17 feet long and weighs 12,000 pounds,” states Feld’s Monster Jam 101 webpage. But it’s hard to convey the sheer scale of both the machines and their bizarreness. It’s the rapper Ludacris rocking up in an oversized pair of Air Force 1s and the arms from his “Get Back” music video. It’s the Magic Kingdom on 650-pound wheels, with a super-charged, methanol-fueled V8 cranking out 1,500 horsepower. In fact, it’s hard not to think of Monster Jam as Disney on Dirt. The cartoonish-ness is disarming. I stand beside Sparkle Smash — the glittering, unicorn monster truck with an ombre mane — utterly disarmed.

Beside each truck is a queue for photos with the truck drivers and their two-wheeled motocross counterparts, who appear during halftime like younger siblings eager to make an impression on a captive audience. As for the main attractions, there’s Monster Mutt (a dog with enormous flapping ears), Classroom Crusher (a school bus with hot-rod flames streaking down its sides), and ThunderROARus (a dinosaur on wheels). It’s not exactly Hot Wheels — which now hosts its own monster truck show, “Glow-N-Fire,” after a falling out between Mattel and Feld in 2019 over licensing rights — but the focus on merchandising is far from subtle. If many of today’s touring musicians and bands feel like glorified T-shirt salesmen, these monster truck drivers must also live with the knowledge that toy sales are responsible for large portions of their salaries.

Already 30 minutes into the fray, I decide to join the line for autographs from the Megalodon team (Jason Statham could never). There is something even more bewildering to me about a shark truck than a unicorn one: a sillier version of a thing that does not exist can only go deeper into silliness, but the goofiest version of one of the most terrifying things to have lived breaks the brain with audacity alone. It is impossible not to giggle.

An announcer interviewing one of the teams on the arena’s loudspeakers mentions that the track is slicker than usual and giving trouble to some riders this week. I pick up a handful of the dirt to examine it, mashing it gently with my middle and ring fingers against my palm. The dirt feels… good? With a little clay in there, even? It’s unexpectedly satisfying to me, though perhaps less surprising to any die-hard fans given that drivers have waxed poetic about the stuff for years.

The good dirt at Monster Jam. Surprisingly moist. (Rahawa Haile/ COYOTE Media Collective)

By now, I have walked the pit three times, and have each time found joyful contradictions. I pass a crayon tent — yes, a crayon tent — on my first lap, and stop on the second to grab a coloring sheet. I mean, why the hell not? The 45 minutes I’ve spent at the Pit Party have been unbearably wholesome. Soon, Rema’s “Calm Down” starts playing overhead, and a part of me wonders if maybe Afrobeats at the Monster Jam is where the War on Cars loses its first battle with children. A boy named Carter offers to trade his pink Crayola for my blue as the song ends. I have to admit it: This Pit Party is arguably my best day in weeks.

On my third lap, it’s hard not to notice just how many families of color are mingling around me. Sure, there’s a white man in an “I WORK HARD SO MY MUSTANG CAN HAVE A BETTER LIFE” T-shirt, but it is nevertheless a hella Black scene. An hour in, I note that the monster truck drivers remain as hyped as they were when I entered, kneeling to greet toddlers with genuine enthusiasm. For as hard as Feld works to bring out the hyper-consumer in every Monster Jam attendee, $20 for a Pit Pass that includes photos and autographs with each monster truck team (and crayons!) feels generous. I could leave this second and feel like I got my money’s worth, and wow, is that some level of capitalist ingenuity — that the main event should feel like the add-on and not the other way around.

Come noon, it’s time for the dirt crew to clear out the pit. I stop by concessions where a 20 oz. Pepsi runs $10, bringing any sense of a steal to a close.

(L) An obscenely priced bottle of Pepsi at the Oakland Arena. (R) A machine smoothing out the track dirt post-Pit Party. (Rahawa Haile/ COYOTE Media Collective)

Then I find my seat and watch a small tractor methodically level the ground. It’s combing the dirt with a grooved attachment as though in a Zen garden. I should have chosen a different career, I think, buzzing with caffeine. I could be raking the monster truck track! Something practical and soothing. “What have I done?” I whisper, enraptured by the mechanized dance of competence.

This temporary peace is interrupted. The Jumbotron flashes a QR code so fans can visit the “Judges Zone” on their smartphones, enter their city code to log in, and then rate each truck’s forthcoming run. We are told to make sure our privacy settings are off; I decide to opt out of voting. I can imagine why the introduction of spectator scoring has rankled longtime fans. Data harvesting concerns aside, it’s a lot of power to give to a six-year-old who just wants to see Grave Digger vroom, regardless of its performance.

Soon, it’s time to celebrate the United States. A U.S. flag lights up on the Jumbotron. “The greatest nation on earth,” says one announcer, as LOCASH’s “Three Favorite Colors” starts playing (spoiler: they’re red, white, and blue). The arena falls silent. A child starts singing the national anthem while a motocross driver in what appears to be a Dalmatian onesie holds a hand over his heart. I am seated. Many of us are seated. The smell of not-gasoline fills the arena (the truck’s circulatory system consists of methanol). The scent is not unlike fireworks. I am awash in star-spangled patriotism.

Then there’s trouble. The Sparkle Smash truck has broken down before the competition’s started and is unceremoniously towed away. I slip my earplugs in as the first truck to roar in finishes with a lap time of 10.067s. It’s an excavator from hell named JCB DIGatron, the same brand as my Zen garden king. I get the impression that everything I see is an advertisement for everything I don’t. Not to be outdone by BART, here there are ads for Zenni Monster Jam glasses. A Monster Jam video game commercial plays above us — one of 10 Monster Jam games in existence. (In August of 2024, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson announced his upcoming Monster Jam live-action Disney film, because of course there would be one of those, too.)

By the way, it is fucking loud. The NIOSH sound level reader app I downloaded the night before calculates a high of about 109 decibels. Soon after, ThunderROARus gets some air after finishing a lap, and during the two-wheel challenge, El Toro Loco, a Latinized monster truck in the shape of a bull, does a handstand before shooting steam through the nostrils on its hood. It’s all admittedly very impressive.

The track is rearranged at halftime with steep ramps for the Freestyle Motocross portion. I know at once something is wrong with the way I’m living because, somehow, I’ve started to doze off while dirt bikers do backward flips midair. Maybe it’s a sugar crash. Maybe nothing compares to the Pit. But then a rider throws pink confetti high above him prior to his stunt and I’m up again, screaming beside a crowd of eight-year-olds.

In lieu of a kiss cam, Monster Jam displays a “Simba cam” on its jumbotron, encouraging parents to hoist their kids skyward like Rafiki in The Lion King. A child seated in front of me lifts a chicken tender high above his head, gripping its tip proudly with both hands.

Finally, it is time for the main event: Monster Jam Freestyle, where all the stops are pulled for every trick you could imagine. Earlier, some friends had asked me whether Monster Jam was staged, and if so, to what extent. Was it like wrestling? The Harlem Globetrotters? Well, it wasn’t scripted, and I know it to be genuinely competitive, because in no way could someone pay me to strap into a 12,000-pound fiberglass chassis and launch myself 30 feet into the air without the chance of winning something.

The conflict, I think, lies in the opportunistic commerce of it all. A dissonant whine between harmonic athletic intent and the pitchiness of vertical integration. It sits atop the whole endeavor like an oil slick. All I can think is poor birds — then I remember Feld owns every bird: Gravedigger, Sparkle Smash (originally a popular die-cast toy, now a monster truck for which there can be new toys), Megalodon, Monster Mutt, El Toro Loco, Classroom Crusher, ThunderROARus, even the inspiration for my zen lord, JCB DIGatron.

Team Sparkle Smash enters the track, quickly ripping through a few drifts and jumps before slowly reversing to attempt its signature backflip. There is a crunch and a collective gasp as it fails to stick the landing. The driver is fine, and no one is hurt, but I find myself feeling sorry that the unicorn and its fans couldn’t catch a break today.

Grave Digger later attempts the same backflip and also lands poorly, with pieces of the truck flying everywhere, its one wheel hanging in the air like a limp white flag. Shortly after, the event ends and we all stream out of the arena.

A month later, some questions remain. Namely, what is so monstrous about monster trucks in 2025? I have seen Cronenberg’s Crash, and Titane, and all manner of weird things happening to and around vehicles in media. Monstrous wasn’t seeing grinning kids standing in front of 66-inch tires at Monster Jam; monstrous was realizing the front hood height of the Ford F-250 parked on the street was just 11” shorter. Was my closest comparison for Freestyle Mania actually the Roman Colosseum? Had I come for the acrobatic feats as much as the fiberglass gore? It left me distraught, this suspicion: that someone who hated trucks might have found an outlet for gleeful destruction among them.

In practice, what I found at Monster Jam was less a fixed event and more a roving echo of place. Sure, the trucks were a constant, but at its core, Monster Jam held a mirror to a city. It is perhaps why my experience in Oakland sits in such stark contrast to a fellow writer’s excursion in Anaheim back in 2017. The monster truck drivers understood this fluidity better than anyone, I suspected, regardless of their political inclinations: Their job, in no small part, was to smile in photos beside fans whether they wore keffiyehs in Alameda County or MAGA hats in the OC. If dirt was matter out of place, as the Mary Douglas quote went, then what I felt in Oakland was the collective wonder of experiencing absurdity in place. (Dirt too, for that matter.)

The timing made sense. We are in an era that rewards harmless absurdity, across the spectrum, with colossal fandoms. One where Savannah Bananas sell out baseball stadiums and romantasy novels top the New York Times bestseller lists. One where we have not one, not two, but three 9-1-1 TV shows by Ryan Murphy, in which children’s bounce castles fly off of cliffs, or kites caught in a powerful gust take kids aloft with them (if you are a child in a Ryan Murphy show, I am sorry).

For years, I’ve unknowingly been primed to have a blast at Monster Jam — at least in Oakland, a city whose communities held me safe and close. Maybe it was more Nicole-Kidman-AMC-ad than I first thought. “We came to [Monster Jam] for magic… because we need that; all of us.”

Even me, it seemed.

Rahawa Haile is an Eritrean American writer from Miami, Florida. Her work covers arts & culture, borders, and the outdoors. In Open Country, her blended memoir about the Appalachian Trail and the politics of free movement in the US, is forthcoming.

View articles