Pass the Rice, and Please Explain Your Genocide

At a thoughtfully organized dinner in Oakland, Palestinian culinary activists shared more than just food — they offered their stories, their resilience, and their patience

At a thoughtfully organized dinner in Oakland, Palestinian culinary activists shared more than just food — they offered their stories, their resilience, and their patience

Water cremation, also known as “aquamation,” is gaining traction as an environmentally-friendly alternative to traditional cremation by fire. But what exactly is it?

The sordid tale of the freelancer who never was.

At a thoughtfully organized dinner in Oakland, Palestinian culinary activists shared more than just food — they offered their stories, their resilience, and their patience

One of the Big Entrenched Food Ideas that I tend to struggle with the most (apart from the seemingly immortal chestnut that immigrant food is only legitimate when it’s cheap) is the concept that people can resolve our differences by breaking bread together. In 2026, I think it’s hopelessly naive to believe this. We’ve seen ICE agents sit down at a Mexican restaurant in Minnesota as customers, only to abduct the staff after eating the food said staff had cooked for them. Over and over again, we’ve watched imperialistic cultures wholeheartedly embrace the food of those they colonized, while the material power dynamics remain unchanged. You and I can eat the same meals, but does that mean we’re friends? It just doesn’t work that way.

So on first blush, the press release I received in January for an educational “Countries in Conflict” dinner seemed like more of the usual — a call for “meaningful gathering” in “ever more polarized” times, in this case by Slow Food East Bay. The organization is the primary Bay Area offshoot of Slow Food International, a storied Italian advocacy group dedicated to creating more space for human-scale food production and heritage foodways.

At the Feb. 8 event held near Lake Merritt, several Palestinian food and drink purveyors and a farmer came together to share their work and talk about the current genocide in Palestine. It was part of Slow Food East Bay’s Cultural Food Traditions Project, which began in 2018 amid the anti-immigrant strains that had reemerged, like a recurring wart, in American politics during Donald Trump’s first term as president. Each of these dinners focused on one culture’s cuisine, with a panel discussion and chances to talk to people of that culture. (Since the current theme was “Countries in Conflict,” the next dinner on Mar. 29 would feature Sudanese food and its makers.)

Something felt off to me about people performing their humanity for an audience while their loved ones were being murdered, oppressed, and systematically made invisible. And yet, I went. Ever the critic (of food, as well as my own presumptions), I like to be proven wrong.

Chef Nikki Garcia of the Cuban-Palestinian pop-up Asúkar produced a heroic feast for the occasion: an extravagant, meat-free maqluba with chickpeas, eggplant, and tender slices of potato layered over steamed rice; shakshuka; mezze served with finger-sized plantain chips; a gorgeous raw vegetable salad with a hefty sprinkle of minced jalapeño; and guava done up in empanadas and baklava.

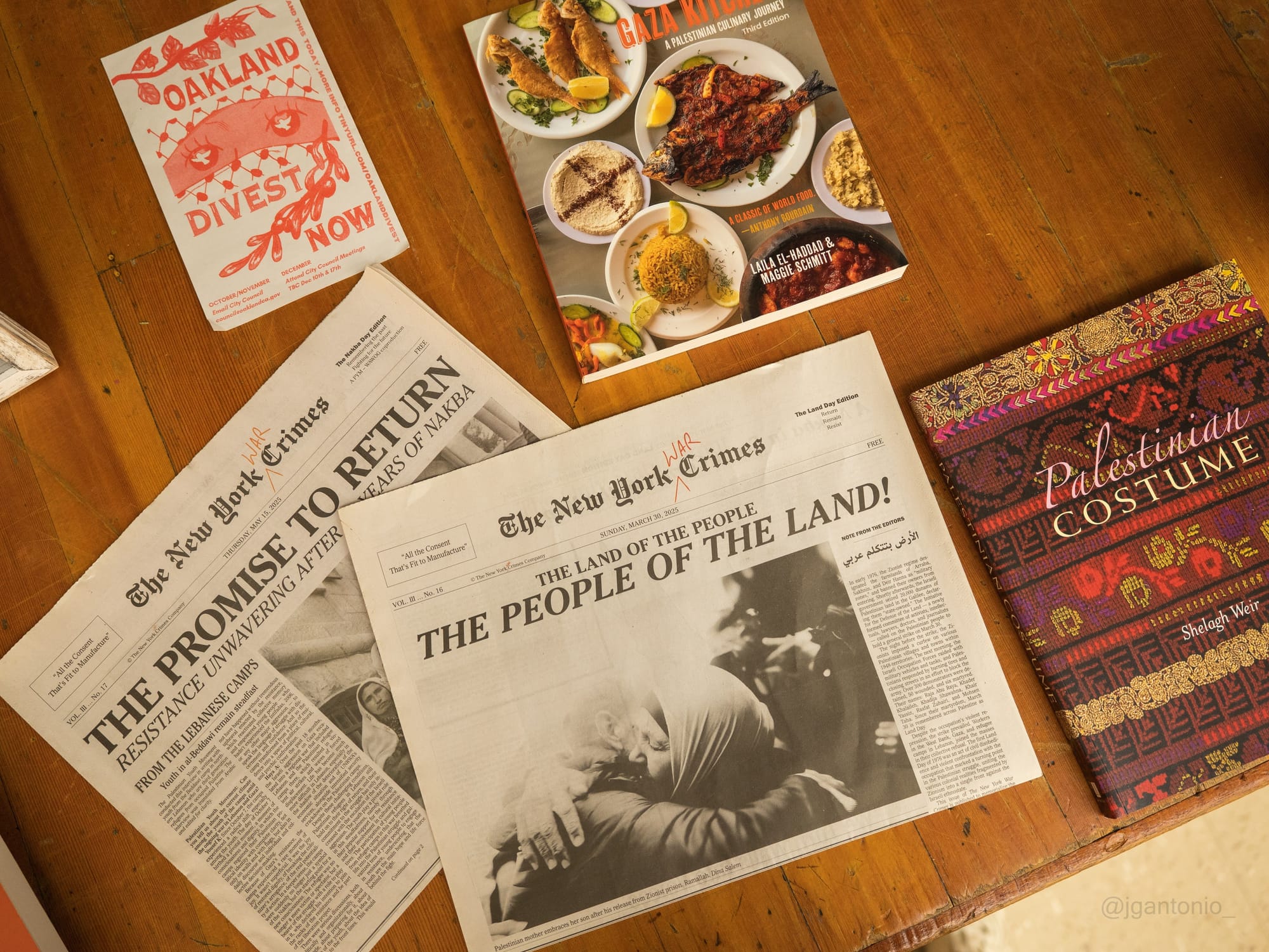

It was clear that so much work and thought went into setting the scene for a meaningful presentation. Each of the featured guests touched on deep and existential frustrations when they took the stage, which was decorated with lush olive branches, books about Palestine, and print copies of the New York War Crimes.

Clockwise from top left: Nikki Garcia's maqluba and shakshuka; empanadas with guava; a mixed salad in a wooden bowl; attendees enjoying the Slow Food East Bay dinner. (Courtesy of Gabe Antonio).

It’s “frankly a miracle” Palestinians can manage to stay sane and try to have normal conversations about everything that is happening to their people, said Nadia Barhoum, whose seed-saving and land stewardship initiative, Thurayya, preserves crops like molokieh with origins in Palestine. A recent article in the San Francisco Chronicle highlighted her work in seed saving, but took pains to note the number of casualties suffered by Israel, down to the single digit, during the Oct. 7 attacks in 2023.

For Garcia, whose December 2025 pop-up at Berkeley Bowl was canceled at the last minute when a few customers complained about her politics, being Palestinian has had numerous professional consequences. Berkeley Bowl has since reached out to reschedule, according to Garcia, but she won’t take up their offer until the company apologizes.

Fathi Abdulrahim Harara of Oakland’s Jerusalem Coffee House has also been harassed by Zionists, most notably when two local men wearing Star of David hats came to the cafe during two separate incidents and antagonized the staff. After employees kicked them out, the story escalated into national news. (In a moment of pure, unadulterated CHUDness after that incident, San Francisco Supervisor Matt Dorsey proudly tweeted about buying the exact same hat as one of the men.) Now, the cafe is grappling with the extreme costs of a discrimination lawsuit brought against them by Pam Bondi’s Department of Justice.

According to Harara, these realities show that “it is an act of love” and enduring faith in humanity for Palestinians to patiently undo all the dehumanizing myths and stereotypes erected around them in place of honest reckonings with their history.

Asking the first question of the panel’s Q&A section, a woman, smiling brightly and standing up with a belly full of Palestinian food, wondered if “both sides” could ever set down their hostilities and live together in harmony. There it was again. I saw a tight smile form on Harara’s face as he listened; yet another wound to privately navigate as the world looked on.

I first began teaching food media at the Slow Food-founded University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo, Italy in the spring of 2024. Between conversations about local olive oil and hazelnuts and the politics of foraging, my students detected nuances between the myriad ways different people spoke about food. There was discontentment with the way the university — and Slow Food as an international organization — refused to acknowledge the horrific escalation in violence that was then beginning to occur in Gaza. In addition to bombing homes, agricultural lands, hospitals, and subsequently, refugee camps, Israel had intentionally stopped food aid from reaching the region. Those who survived the military’s violence were starting to die of starvation.

My students rightly pointed out that Slow Food’s advocacy for foodways that were “Good, Clean, and Fair” seemed to falter when it came to questioning the ways in which food access was an integral element of the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Like many of their peers in the United States and elsewhere, the students, who formed the school’s first social justice group that year, pressed their university to call for a ceasefire, divest from Israeli companies, and host Palestinian chefs and thinkers for on-campus events. Though the group was able to hold a student-led teach-in on campus, neither the university nor Slow Food openly acknowledged their concerns at the time. The university finally published a statement about Gaza from Slow Food’s founder in May of 2025, though it made no public commitment to change its own relationship to Israel.

Given all this, it’s encouraging to see a Slow Food offshoot in the Bay do what it can, dedicating space to people who’ve often been sidelined by its parent organization. And the event I went to succeeded (with flying colors!) in its stated aims, and it was doing actual good in the world: The proceeds from tickets and donations were split between the featured purveyors and Gaza Great Minds, an NGO bringing normalcy and education to children enduring the genocide.

I hope Slow Food East Bay can continue to host more events like these. But a part of me still feels angry for Garcia, Barhoum, and Harara on principle. I wanted the whole room to sit with them, to tear out our hair and mourn together. Instead we sat politely and clapped. It felt almost obscene, even if the hosts had done their best to create a welcoming environment for genuine discourse.

But a host can only do so much in wretched times like these.

As I walked out, I overheard the woman from the Q&A cornering Harara at the coffee counter: “Are you saying October 7 didn’t happen? Are you?” Other guests had gathered around her, attempting to rein her in. I’m sure if she’d belched, she’d be able to taste the maqluba she was just beginning to digest.

Maybe, beneath my cynicism, I do want breaking bread to be enough to fix everything. I'm sorry that it isn't.

Soleil Ho is a cultural critic, cookbook writer, and food journalist who has a nasty habit of founding media projects instead of going to therapy: from the feminist literary magazine Quaint to food podcast Racist Sandwich to our dear COYOTE.

View articles