How Racket, Minneapolis’s Worker-Owned Newsroom, Is Covering Its Hometown Fascist Invasion

“This is the worst fucking time. But watching people’s response to ICE has been the most affirming thing in the world.”

“This is the worst fucking time. But watching people’s response to ICE has been the most affirming thing in the world.”

This week we've got strikes, slime, white rappers, psychics, goth nights, and more.

It’s time to stop waiting around for those in power to save us. We, the people, can get everyone’s basic needs met.

Known for decades of shows at Madrone and the Boom Boom Room, the musician and mentor suffered a stroke last week, just before his 81st birthday. A fundraiser aims to get him back on his feet.

There are a few things you can always depend on in San Francisco — markers that situate you in time, in a year, in a neighborhood. Bacon-wrapped hot dogs in the Mission late on a Saturday night. Tourists, freezing in T-shirts, walking the Golden Gate Bridge in June.

Up until two weeks ago, you could stroll into Madrone Art Bar on Divisadero on Tuesday evenings and come face to face with a musical legend leading the best weeknight dance party you’d ever seen. Oscar Myers is a charmingly no-nonsense trumpet player, percussionist, singer, and bandleader who’s performed with James Brown, Charles Mingus, Ike Turner, and Ray Charles, among others. Now 81, Myers has held court at Madrone with his band Steppin’ nearly every Tuesday for the past 17 years. Before that, the musician — a Vietnam veteran with a Purple Heart — led the Tuesday night funk jam at the Boom Boom Room, beginning when John Lee Hooker first opened the club in 1997.

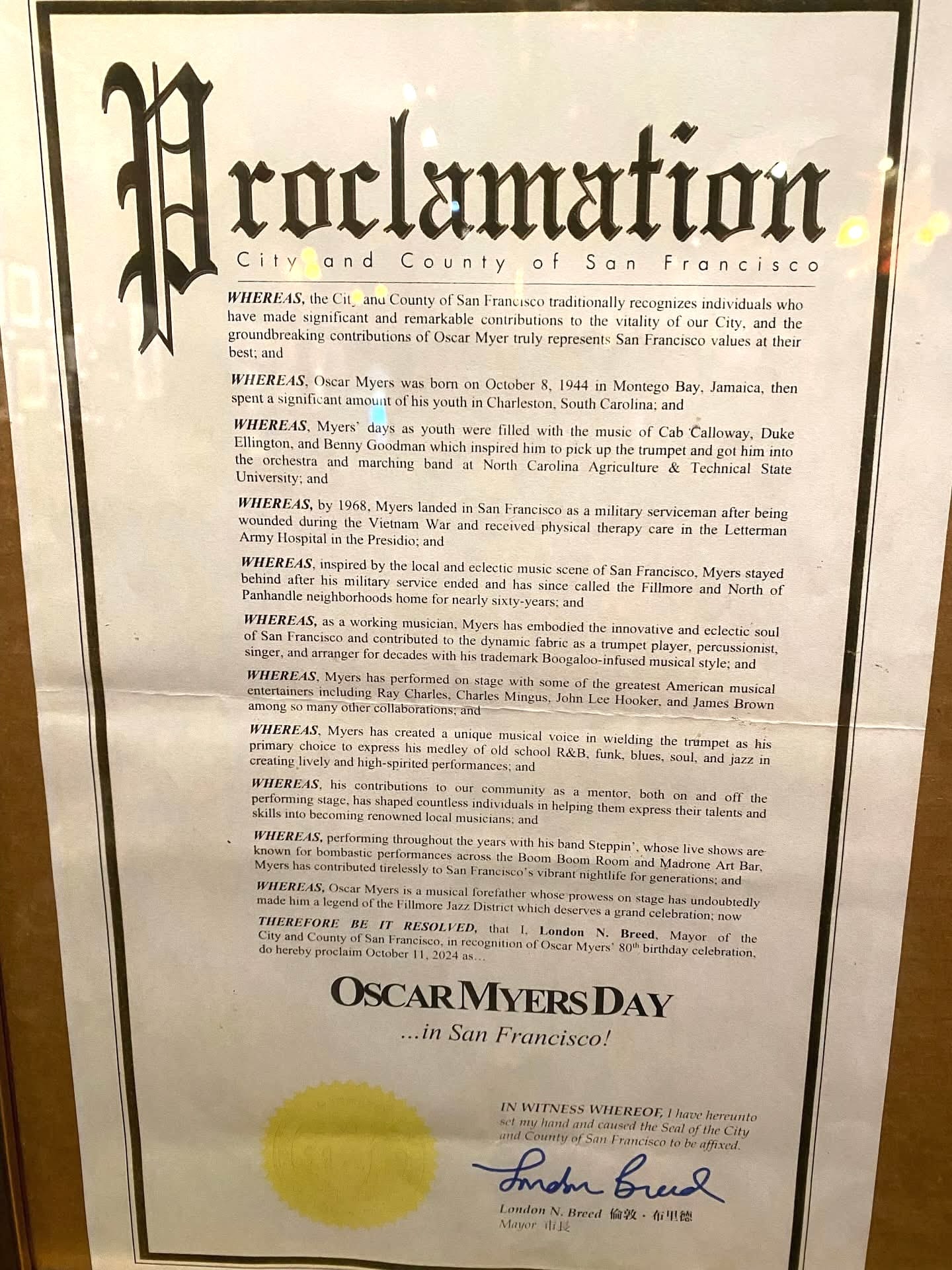

But Myers wasn’t at Madrone or the Boom Boom Room this past Tuesday, nor the Tuesday before that. The musician suffered a stroke on Oct. 7, the day before his 81st birthday — and four days before “Oscar Myers Day” on Oct. 11, as officially decreed by the city of San Francisco in 2024.

Michael “Spike” Krouse, Madrone’s owner and a friend of Myers for more than 30 years, says he is stable and coherent, but faces a long road to recovery. Challenges include new mobility issues — such as weakness in his right hand, which he uses to play the trumpet. He lives in a fourth-floor walk-up apartment, has no children and not much of a financial safety net, according to those who know him best. Live performance has been Myers’ bread and butter for more than half a century.

So now, as Myers recuperates at CPMC Davies hospital, Krouse has launched a fundraiser to help cover rehabilitation therapy, in-home care and mobility support, transportation to therapy and other appointments, and living costs while Myers is healing. The hope, says Krouse, is that the community will rally around a man who has given an invaluable gift to San Francisco.

Indeed, Myers’ role in the scene is a special one: Beyond the surface-level good times at a Steppin’ show, he’s provided audiences and artists alike with an increasingly rare connective thread to the Fillmore’s musical heyday, a time when it was known as the Harlem of the West. To up-and-coming Bay Area musicians, he’s been a tireless mentor.

“Oscar was a big part of my musical upbringing, and he definitely took me under his wing,” says Wil Blades, a widely acclaimed organist who came up at the Boom Boom Room in the early 2000s. Blades, who became a regular performer at the club before he was legally old enough to drink, first occasionally sat in with Myers’ band Blues Beat. He eventually took over the organ chair when organist Louis Madison — who wrote and performed on several James Brown hits — was in ill health and couldn’t play.

“At the time, his band was all super-seasoned vets that had played with freaking everybody, and it was sink or swim,” says Blades of those Tuesday night shows. He remembers Myers setting up next to Blades’ chair on stage; throughout the night, Myers would play his trumpet with his right hand, and with his left hand, he’d hold up chord symbols so Blades could follow along.

“Not only is he directing the band, being the leader, [interacting] with the audience, he also has this young kid who doesn’t know the songs, and he’s teaching me,” says Blades. “It was a huge learning experience for me. And it was particularly gracious of Oscar, knowing some of the discrimination he faced in life, to let a 20-year-old white kid play with this band of all Black, serious, veteran musicians. I think that speaks to his character.”

When Krouse, who had helped open the Boom Boom Room, took over Madrone in 2008, Myers picked up Tuesday nights there with his new band, Steppin’, which featured younger players like Blades.

“The man has given so much,” says Krouse. “Both as a veteran, fighting for the country, and with his performance and his contributions to San Francisco. Here’s a time and a place where he needs our help. I want to make sure we don’t let him slip through the cracks.”

Born in Montego Bay, Jamaica in 1944, Myers grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, where his father worked as a gravedigger. Myers picked up the trumpet as a young teen, then played in the marching band at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, alongside soon-to-be saxophone legend Maceo Parker.

In Vietnam, Myers served as a “tunnel rat” — an extra-dangerous job that involved climbing through Viet Cong tunnel systems to find and disarm explosives — in part because he was small in stature. He’s never liked to talk about his time in the Army, but friends say it’s clear he experienced things that resulted in PTSD. After being wounded in the 1968 Tet Offensive, he landed at Letterman Army Hospital in the Presidio for rehab, and quickly decided to stay in the city.

“The Bay Area was humming,” Myers said of that time in a 2014 San Francisco Bay Guardian profile. “There was music coming from everywhere.”

Over the next 30 years, Myers became a pillar of the Fillmore scene, playing with a who’s who of local jazz, funk, soul, and boogaloo musicians — as well as some international stars. In the early ‘90s, he played eight gigs with James Brown, who famously fined his musicians for missing notes: “All that’s true,” Myers told the Bay Guardian. “He’d go down to the front of the stage and be leaning and crying and singing and then he'd hold up his hand: $5.” (Myers clarified that he never personally had to pay up.)

As a mentor, Myers may have picked up a thing or two there: Those he’s taught will tell you he gives young musicians a chance, but you’ve got to be humble, and you’ve got to put in the work. “He definitely comes from that James Brown school of ‘You do it my way, or you get the fuck off the stage,’” says Krouse with a laugh.

Blades says Myers chewed him out a handful of times for various errors, but that was part of how he showed love. “I knew how to take it, and he saw my hunger to learn and approach the music the right way,” says the younger musician, who’s now in his 40s and teaches music lessons in addition to performing. “I have a young student who got chewed up by a drummer recently, and I was trying to explain to him that he wouldn’t have done that if he didn’t care. That’s just part of the tradition of mentorship.”

That attitude extended beyond young artists, too. Myers could get away with colorfully berating the audience at a show — generally for not dancing enough — while still somehow coming off as irrefutably likable, an ever-present glint in his eye.

In 2024, while gearing up for Myers’ 80th birthday party at Madrone, Krouse contacted the city to see about getting an official Oscar Myers Day on the calendar. “I reached out and basically said, ‘Hey, he’s the last one,’” says Krouse. “I don’t know of any others that are still around doing what he’s doing, still playing every week. And it’s time the city recognizes him as one of the greats.”

The proclamation issued by then-Mayor London Breed describes Myers as “a musical forefather whose prowess on stage has undoubtedly made him a legend of the Fillmore Jazz District which deserves a grand celebration.” It also notes that his “contributions to our community as a mentor, both on and off the performing stage, has shaped countless individuals in helping them express their talents and skills into becoming renowned local musicians.”

To an audience member, on a week-to-week basis, that mostly looks like a really good band having a really good time. At Madrone, over the last 17 years, regulars at his Tuesday night residency were accustomed to hearing a few signature Oscar Myers quips, such as “You want something slow, something fast, or something half-assed?” or “The more you drink, the better we sound!” before he launched the band into the next Curtis Mayfield or Melvin Sparks tune.

“He’s a working man’s musician,” says Krouse. “He’s old-school and he’s one of a kind, and he’s put smiles on so many people’s faces. If you’ve ever laughed or danced at any of his performances on Tuesday night at the Boom Boom Room, or Tuesday night here [at Madrone], or at the Fillmore, or at Jazz Fest,” he says, it’s time to return the favor and support Myers.

In 2014, Myers said he had no plans for retirement — “until I croak or I can’t move, then I’ll call it quits.”

Krouse is concerned for his friend, but he doesn’t think Myers is necessarily there yet. With proper support and rehabilitation, he’s hopeful that some Tuesday evening in the future, San Franciscans will be able to wander into Madrone and find that Myers has made a triumphant return to the stage, where he belongs.

“He’d always sing ‘take me to the bridge,’” says Krouse. “And he took us there. He took us there a million times. Now it’s our turn to take him there, you know?”

Emma Silvers is a San Francisco journalist with 15+ years of experience covering the people and policies shaping arts and culture in the Bay. She grew up in Albany and lives in the Mission.

View articles