Some Google Searches I, a San Francisco Parent, Have Done In the Past Week

I’m sleeping great, how about you

I’m sleeping great, how about you

Ten years ago, protesters took to the streets to slam San Francisco’s Super Bowl City and call for an end to homeless sweeps. As the game returns to the Bay this week, why are things so quiet?

This week we've got dunes, vintage animation, fonts, and paper fruit.

Ten years ago, protesters took to the streets to slam San Francisco’s Super Bowl City and call for an end to homeless sweeps. As the game returns to the Bay this week, why are things so quiet?

In January of 2016, three weeks before the 50th Super Bowl was played in Santa Clara, ten 1,600-pound “50” statues appeared around San Francisco. It was the first time a Super Bowl had been held in the Bay Area since 1985, and the first time it would be played in the 49ers’ Levi’s Stadium, the NFL’s newest, shiniest toy.

The tourism board and local politicians hyped the “golden anniversary” of the game, and the city poured money into promoting it: for example, a cool $5 million on “Super Bowl City,” a 10-acre temporary village at Justin Herman Plaza on the Embarcadero, complete with a puppy bowl replica and a zipline down a tiny model Golden Gate Bridge.

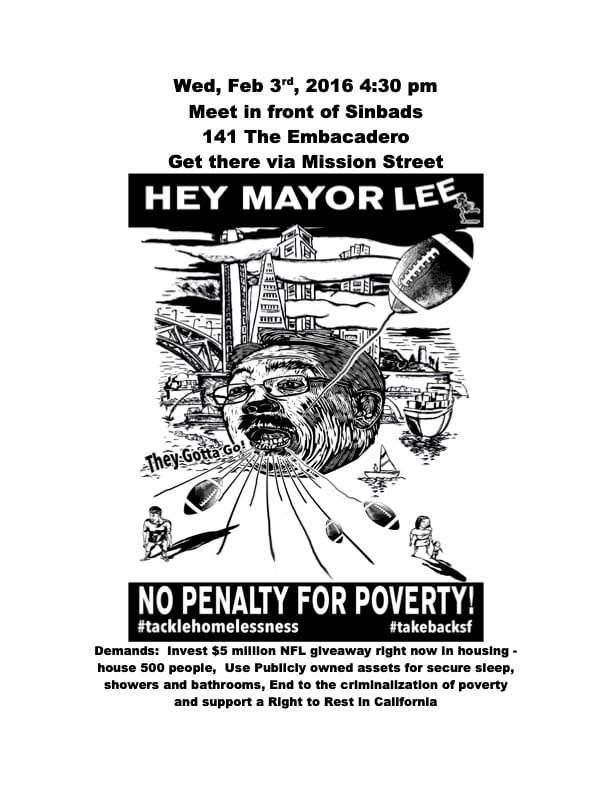

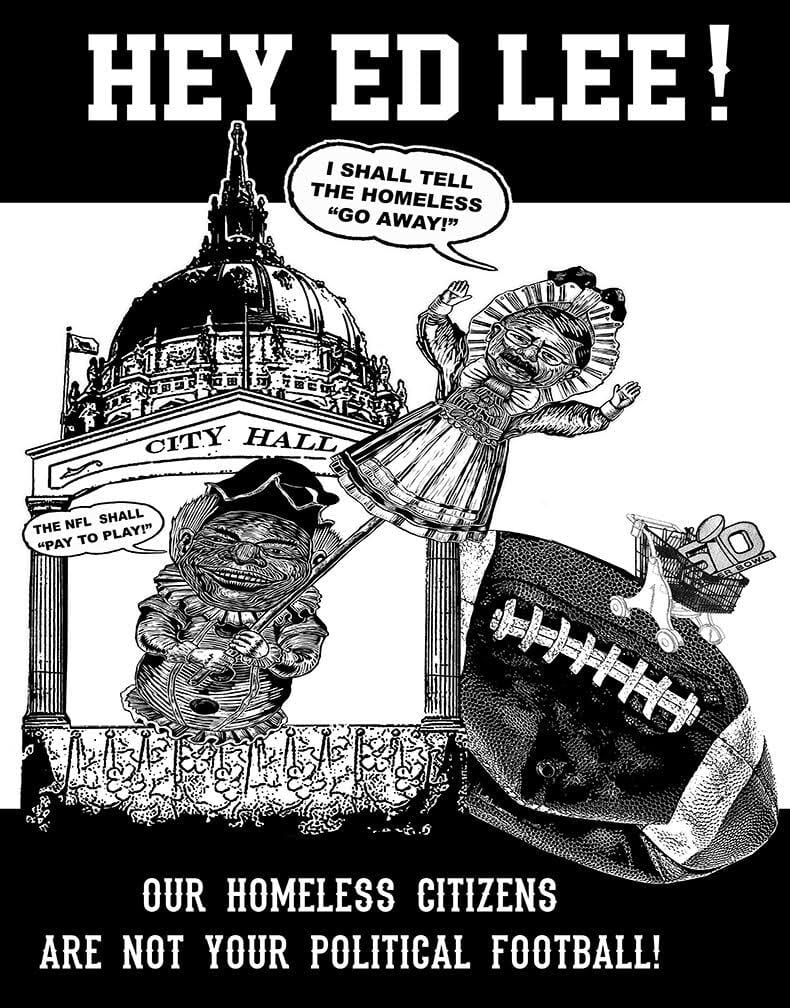

At the same time, city workers began clearing unhoused folks from the streets around the Embarcadero, Market Street, and downtown, throwing their belongings in the trash and pushing them into other parts of the city. Word quickly spread among the city’s homeless advocates, and San Franciscans turned out to protest the week before the game. On Feb. 3, hundreds of police officers in riot gear descended on the Embarcadero to quell one such event — and national and international news outlets took off running with the story.

But for average residents, the fate of those statues had already summed up the way we were experiencing the Super Bowl: as an invasion, an unwelcome party at which the city threw millions in the name of tourism — and without the consent of its taxpayers. Within days, the “50” in Alamo Square Park was spraypainted, knocked over, and had its metal edges ripped off and its solar panels smashed. There were complaints that its presence wasn’t greenlit by neighborhood groups and its installation didn’t follow the standard bureaucratic process. After two weeks of abuse, it was quietly hauled away.

Ten years later, we’re once again staring down the Super Bowl in the Bay Area. But this time, there are no national headlines about our homeless sweeps, no posters slapped on lampposts calling out the mayor for his regressive policies, no protests planned to resist the idiocy of forcibly displacing people from the streets when they have nowhere to go, no national news outlets calling up our local organizers for quotes on the resistance.

It’s worth asking: As the city drops millions of dollars on yet another massive sports event, what’s different this time? Where’s the resistance?

Flyers for the Feb. 3 protest slammed Mayor Ed Lee for sweeping homeless camps. (courtesy Coalition on Homelessness)

It’s true the climate was different then. The Board of Supervisors had a progressive majority, and there was opposition to corporate giveaways like the unpopular Twitter tax break. Sweeps happened, to be sure, but politicians’ anti-homeless rhetoric wasn’t as blatant — or at least as openly cruel and dehumanizing — as it is now. So in August 2015, when Mayor Ed Lee said plainly that homeless people in the vicinity of Super Bowl City were “going to have to leave,” there was a righteous, mid-2010s gasp. It was shocking and headline-worthy.

Compare that with the tone adopted by his successor Mayor London Breed, who in 2021 ranted about our need to be less tolerant of a “reign of criminals” and the “bullshit that has destroyed our city.”

Five years after those comments, the narrative — and perhaps the average San Franciscan’s view of their homeless neighbors — has grown even more aggressive. Mayor London Breed cracked down hard on camps during her tenure, normalizing the practice. “We are going to make them so uncomfortable on the streets of San Francisco that they have to take our offer [of shelter],” she said at a press conference in 2024.

Sweeps have become so commonplace, in fact, that Gov. Gavin Newsom frequently uses them as a political tool to bolster his image. “There’s no more excuses,” he said in a staged video in 2024, using a trash picker to shove pieces of cardboard into an orange trash bag.

Today, we have a moderate majority on the Board of Supervisors, and the mayor is a millionaire desperate to lure in private money and build alliances with the business elite. And yes, that means regularly sweeping homeless camps. It’s happening under this mayor as it’s happened under past ones — you probably just don't hear about it as much. Which is to say, the sweeps haven't changed. San Francisco has.

In 2016, the morning after Macy’s put on a fireworks show to celebrate the upcoming game, swimmers in the Bay navigated mountains of leftover debris. It eventually washed up in Aquatica Park, infuriating park officials.

Claims that the city would recoup the funds it spent in tourism dollars were met with skepticism: San Francisco was fresh off the 2013 America’s Cup, which — despite revolving around a sport that caters to the extremely wealthy — left the city $5.5 million in the hole. While Santa Clara negotiated a reimbursement plan with the NFL for hosting the Super Bowl, San Francisco did not.

The aggressive homeless sweeps were, for many progressives, the straw that broke the camel’s back. Friedenbach saw it happen firsthand. “They were clearing out all the major arteries coming into the city, and they went pretty hard,” she remembers.

As the Super Bowl drew closer, homeless advocates organized a march and protest, calling foul on the city for bankrolling festivities when it had thousands of people sleeping on its streets.

Stuart Schuffman of Broke Ass Stuart, who had run for mayor the year prior, helped organize the protest after witnessing the mass displacement of homeless people downtown. “It was only a few years into the tech 2.0 boom, and there was a lot of anger around that,” he says. “We were organizing locally, and Facebook was a big thing. Social media algorithms were not nearly as evil, so it made it easier to organize that way.”

On Feb. 3, a few hundred people hit the Embarcadero, calling for greater investments in affordable housing and homeless resources. The city grossly overreacted: Police in riot gear stood around en masse, outnumbering the protesters and burning through overtime. Snipers hung out on top of buildings. National media was on the scene to pick up the story.

The Super Bowl festivities continued unchecked, of course. But San Francisco homeless rights organizers made a splash, and for a moment, held a big megaphone.

“I was being interviewed by publications from all over the world,” Schuffman says.

“We got so many people reaching out to us about what was happening here,” Friedenbach says. “I don't understand why it got so much national attention, but it certainly did. Sometimes that's just how it is with movement, where you do work for a million years, and then it takes off.”

Of course, this time around, there’s some other stuff going on at the national level. We’re arguably in the middle of a right-wing government coup. Federal immigration agents are kidnapping children and shooting people in the street (with mixed reports of ICE agents blitzing the region leading up to this year’s Super Bowl). On top of that, our country may invade Greenland?! As always, we are being swept along in a miserable, never-ending daily news cycle that is designed to exhaust us — and it does. As for the lack of Super Bowl resistance, maybe a football game just isn’t our biggest national concern right now.

“The Super Bowl seems like a quaint thing to protest during a civil war,” a friend told me, and he’s right. No one has the energy to fight the “Super Bowl Experience” at the Moscone Center in SoMa this year, and really, should we? It’s 2026; the city bending over backwards to appease huge corporations is par for the course, and no one is raging about its spending on the event. An obsession with San Francisco’s downtown “recovery” has greenlit anything that has the potential to bring in cash.

Meanwhile, the political tone around homelessness has also changed nationally: With Grants Pass in 2024, the Supreme Court ruled that punishing people for sleeping outside was legal, even if they have nowhere else to go.

And then there are the ways the sweeps have “worked” — that is, they’ve been relatively successful at removing homeless people from the area around the convention center and pushing them elsewhere. “When was the last time you saw an encampment on the streets around Moscone?” I asked a friend who works in homeless outreach. “COVID?” she guessed, harkening back to that brief period where the city paused sweeps early in the pandemic.

It makes sense that it’s tough to summon righteous outrage when a human rights violation is so commonplace you barely see it, so normalized that it barely merits a mention in the press. There is a slippery slope here, however. The intensity of our national crises cannot distract us from our local ones, and we can’t become complacent about the cruelty inflicted on our homeless neighbors every day. Any argument that civic issues of homelessness and poverty are insignificant in the face of larger-scale attacks is simply not true. We still need to be protesting and recording and fighting for everyone’s human rights, even if they’re not as immediately deadly as an ICE agent pulling a gun on a woman in her car.

San Francisco’s 2016 protest resisted many of the same things we’re fighting against today: those in power inflicting harm upon our most vulnerable citizens in the streets; our government’s penchant for pulling out all the stops to appeal to powerful corporations; the dispensing of taxpayer dollars on frivolity while people suffer. This battle is ongoing, takes different forms, and we need to continue showing up wherever we can, whenever we can.

And while we’re at it, there’s nothing wrong with vandalizing an ugly statue.

Nuala Bishari is an investigative journalist and opinion columnist who's reported on the Bay Area since 2013. She writes about public health, homelessness, LGBTQ+ issues, and nature.

View articles