Napa’s Biggest Black Culture Festival Didn’t Pay Several Chefs Until They Threatened to Sue

Blue Note's Black Radio Experience drew sold-out crowds to Napa Valley. Months later, some contractors were still chasing their money.

Blue Note's Black Radio Experience drew sold-out crowds to Napa Valley. Months later, some contractors were still chasing their money.

Oakland historically lacks soccer fields. But a group of local players and community advocates hopes to kick off a brand-new space — featuring soccer, coffee, retail, and more.

This week we've got a Donna Summers book club, vegan dinner and a movie, a community bake sale to fight ICE, and more.

Staff at San Francisco’s Rainbow Grocery reflect on collectivity, retail personhood, and an aesthetic disagreement that ended in a fistfight.

This story is part of a new series in which we shine a spotlight on the Bay Area’s many worker-owned cooperatives.

Gordon “Zola” Edgar, a renowned cheesemonger at San Francisco’s Rainbow Grocery Cooperative, remembers a co-worker at the store’s front desk who, when a customer demanded to speak to a manager, ducked behind the counter and popped back up: “Hi, I'm the manager. Can I help you?”

Edgar laughs telling the story now, 31 years into his tenure at the store. He doesn't recommend the tactic (it tends to escalate things). But the tale does capture something essential about working at a place where Karens drift through the aisles like hungry ghosts, aimless without a manager at whom to direct their ire. At Rainbow, the buck stops with the 200 or so worker-owners.

One drawback, on the other hand, is that you can’t complain to your coworkers about your crappy boss, Edgar says. “You have to come to the realization it's all us.”

Rainbow Grocery celebrated its 50th anniversary this year, a half-century of what Edgar calls “a bunch of weirdos just trying to run a business together.” The massive green warehouse store on Folsom Street — home to buckets of organic bulk kimchi, stacks of farm-sourced produce, and this writer’s favorite cheese (Milton Creamery Prairie Breeze, FYI) — operates as a worker-owned cooperative. Every decision, from the temperature of the store to how profits get shared at the end of the year, goes through its members.

Jacob Medrano, who works in produce, was drawn to Rainbow specifically because the job listing referenced the store’s “non-hierarchical structure.” After years at Whole Foods, the idea of not shrinking themself to fit the “standard American” workplace vibe felt radical. Still, Medrano was skeptical: “A lot of businesses say their mission and values, but in reality, that is not how it's like on the floor.”

Making even small decisions had felt like such a huge deal at a corporate grocery store that Medrano wasn’t quite sure how autonomous they could actually be at Rainbow. One day, they asked a colleague where a certain type of produce should go — on this display or that one? “They were like, ‘You can choose. This is your part.’ And I was like, what? I'm able to put it wherever I want to put it.”

The autonomy extends beyond produce arrangements, of course. The walls of the back offices are plastered with worker-owner policies, committee assignments, schedules, and surveys about potential changes that staff need to vote on or respond to.

Yesenia Ochoa, who recently transferred to Rainbow’s human resources department after six years working in the store, came to the co-op from Instacart. At that job, she had asked her manager repeatedly for quality-of-life changes for employees. The response was always, “Yeah, yeah, sure,” followed by nothing, she says. She quit to apply at Rainbow, even though it paid slightly less.

The difference was a revelation: She remembers a time early on in her tenure, when she was working on orders at the store, and a cashier invited her to share her ideas: “We're having a meeting as a department upstairs in a couple of minutes to make some decisions about how we're running [it],” she recalls them saying.

Her first major project: helping start an e-commerce department that would enable Rainbow to sell products online. It didn’t take off the way she’d hoped. But the experience pushed her to join more committees, run for more positions, and take on more responsibility in shaping how Rainbow operates.

(L to R) Shirts, hats and tote bags sold in-store at Rainbow Grocery. (Amir Aziz/COYOTE Media Collective)

Of course, running a business with 200 co-owners can be slow going. Workers call it “Rainbow time” — the pace at which collective decision-making happens. Someone raises an issue, wraps their head around how to fix it, and brings it to their department or a committee or the whole store membership. Getting back to customers about a simple question can take a couple weeks.

But the customers, Edgar thinks, sense the difference from regular grocery stores: Without top-heavy corporate control, the power balance shifts, and the relationship with store staff feels less transactional. Not everyone who shops there knows about the cooperative structure, but enough do that the dynamic shifts. “I actually do feel like the customers are a little more scared of us than they would be at a normal store,” he says. “Because they kind of know there's not some boss they can just appeal to. And I'm not saying it's good— I'm not saying they should fear us.” But, he noted, back in the day, when the store was smaller and the community more close-knit, customers treating staff like servants instead of fellow community members “led to a LOT of friction” — to put it nicely.

Medrano notices it too. At Whole Foods, customers treated them like a computer: where is this, show me that, no greeting. At Rainbow, people say hello, ask Medrano how they’re doing, and share with pride that they've been shopping there for 20 years. Medrano has watched babies in strollers grow into toddlers. On Father's Day, they wished a customer well. “That's the sort of thing that would be weird at a normal retail grocery store,” they said. “They'd look at you like, ‘Have you been staring at me?’”

Edgar has been at Rainbow for more than half the cooperative's existence, making him what the 50th anniversary party organizers called a “Rainbow elder" — though he bristles at the term. When Edgar hit 20 years, he was only ranked 60th on the running list of longest-employed worker-owners. So many people had been there over 20 years that it wasn't remarkable.

The collective has, of course, run into problems. When Rainbow moved to its current location on Folsom Street in 1992, the worker-owners had to decide what color to paint the store building. Edgar recalls having to break up a fistfight that erupted between two staffers over the color: terracotta versus forest green. The solution was to hand off the decision entirely. “Because it was so heated, the board just asked the contractor to paint it whatever color they wanted.”

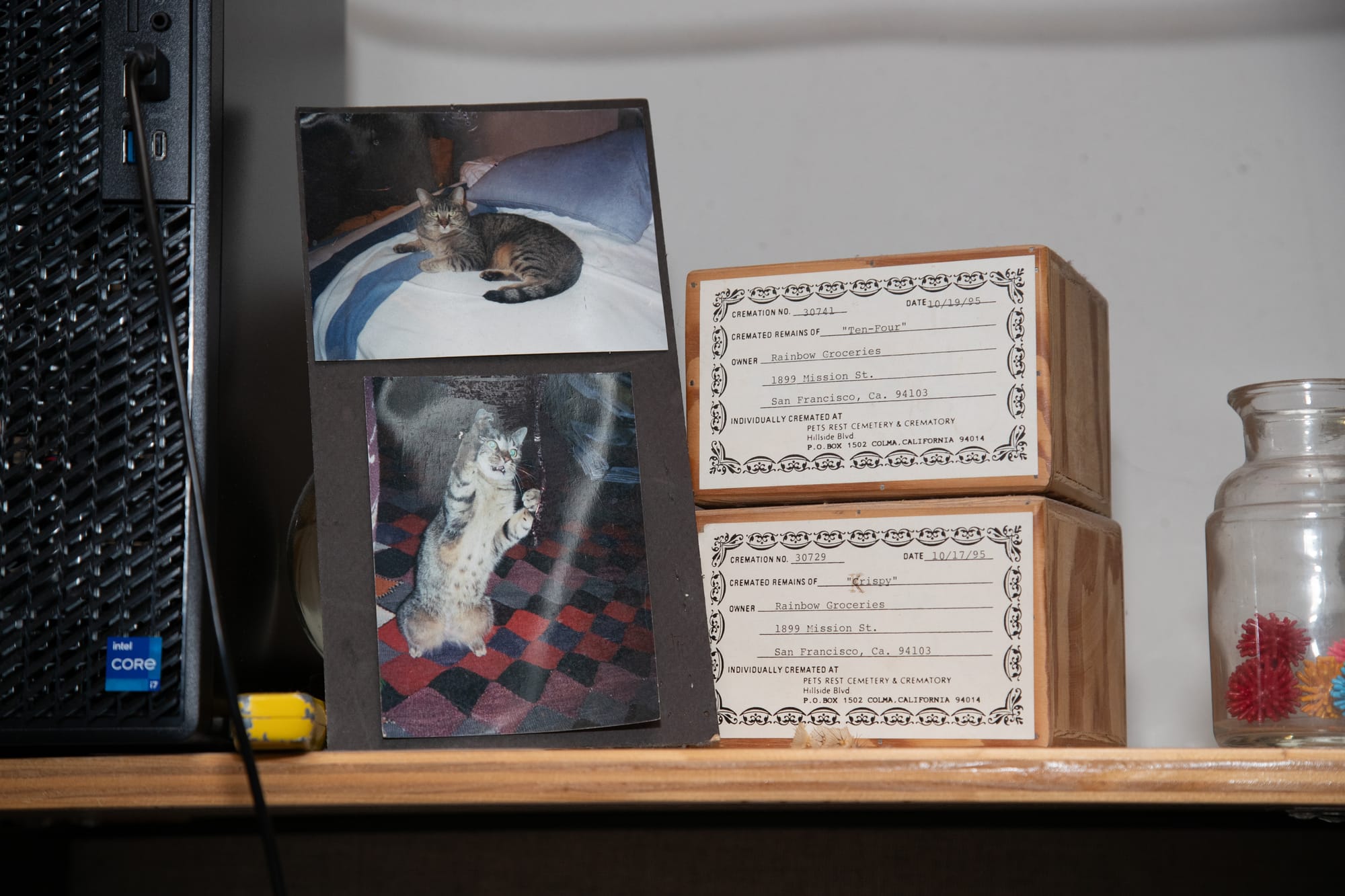

Then there are tales about the store’s various cats over the years — names include Crispy and Ten-Four — who used to handle pest control at Rainbow’s previous location. (For the record, Edgar says, pests aren’t an issue at the Folsom store.) Prior cats’ ashes are still in the store, perched above a desk in the back.

Rainbow oldheads might also recall that Halloweens used to get so elaborate — haunted houses, the cheese department transformed into a butcher shop with fake blood splattered everywhere, and signs advertising German Shepherd meat for 50 cents a pound — that kids cried and Rainbow had to scale it back.

Edgar, who worked in political collectives before Rainbow, came in skeptical about workplace democracy 31 years ago. He still is, a little. The flip side of all that freedom: you can't turn problems over to someone else. Sometimes it works slowly, and sometimes it's hard on people. “But,” says Edgar, “it works in general.”

Why do people stick around for so long? Sure, it’s the empowerment of being a worker-owner — but also, the Rainbow lore is just too good.

Soleil Ho is a cultural critic, cookbook writer, and food journalist who has a nasty habit of founding media projects instead of going to therapy: from the feminist literary magazine Quaint to food podcast Racist Sandwich to our dear COYOTE.

View articles