“Spray Area”: The Evolution of Airbrushing in the Bay

Airbrushing once offered local artists a full-time income; nowadays, it’s mostly a creative side hustle that recalls a nostalgic past. Here’s what the remaining artists have to say about it.

Last year, my wife and I left our hometowns in the Bay Area to live in Mexico. As millennials born and raised in the Bay, we said goodbye to our beloved coast more than once: We crossed the Golden Gate Bridge together, kayaked the shores of Alameda, and dined at our favorite Thai, Ethiopian, and Peruvian restaurants (you don’t know how life-giving California’s culinary diversity is until you’ve left).

The most significant memory from that whirlwind month was visiting the San Jose Flea Market. There, we got our son an old school airbrushed t-shirt with his name artfully spritzed in elegant, sweeping letters across the toddler-sized chest fabric. The task took less than 20 minutes. But symbolically, it gave us hope that our son might one day remember the same version of the Bay Area that we do: one in which artists and working- and middle-class families could make a decent living.

It was a rite of passage to get him personalized airbrushed gear — a memento that harkens back to the Bay Area of the 90s and aughts, when my wife and I, Mexican Americans living in a pre-smart phone society, could get our sneakers, jeans, and shirts airbrushed at malls, county fairs, Great America, and of course, flea markets.

Much of the culture and community from that era has faded, or even completely vanished in today’s dysfunctional maelstrom of tech-fueled capitalism. When’s the last time you had your shirt airbrushed by hand at the Great Mall? And yet, if you know where to go, you can find remnants of our airbrushed past, replete with artists who have adapted and evolved in wildly fresh ways.

A throwback that is still throwing back

There is no official scripture on when and where airbrushing actually began in the Bay, but in asking a few of the Bay Area’s foremost airbrushing experts — one of whom has been doing it for nearly half a century — I learned the artform had started to grow in popularity as early as the late 70s. It became most visibly mainstream throughout the 80s and into the 90s.

“I graduated from Santa Clara University in ‘79, and I wanted to be a painter; but I didn’t get into airbrushing at first,” says Everett Regua, a 68-year-old airbrusher who is still active in San Jose. “I wanted to do a painting with a sunset, and someone suggested using an airbrush to make it easier. That’s why I picked up the airbrush: to get a good blend of colors. And then it just grew from there to do shirts and other stuff. That’s when I started pursuing the Capitol Flea Market in San Jose, and I had a space there for quite a while.”

Regua, a Chicano born and raised in San Jose as one of seven children, represents the vanguard of traditionalists — a taciturn gentleman who speaks loudly with his hands, which have gripped countless airbrush mechanisms over the years and sprayed thousands of items for a diverse clientele all over the greater Bay Area.

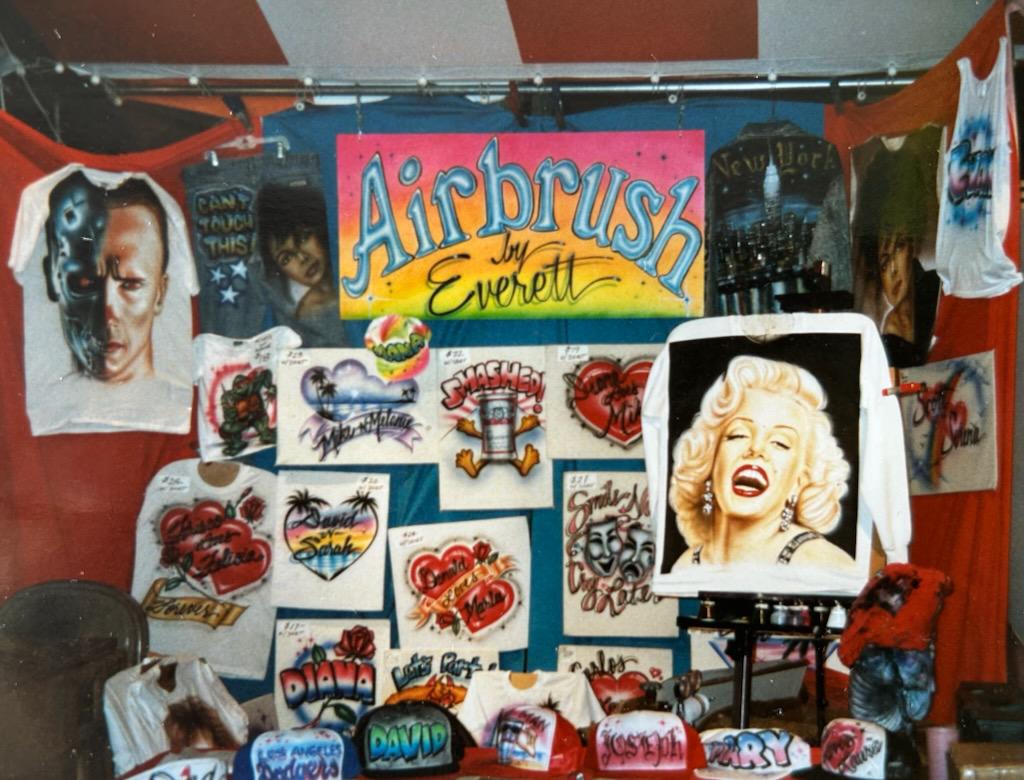

Nowadays, Regua is the only full-time airbrusher at the San Jose Flea Market on Berryessa Road, where he retains a small shop and does the majority of his airbrushing on the weekends in between his regular gig as a sign painter. Regua — who has been at the Berryessa location for decades — tells me that at its pinnacle, the market had no fewer than ten airbrushers working various stalls, each with a steady demand of customers who wanted items customized. In those years, Regua also worked with various lowrider clubs and event organizers, which allowed him to live comfortably by spraying La Virgen de Guadalupe on the candy-flaked hoods of Chevy Impalas.

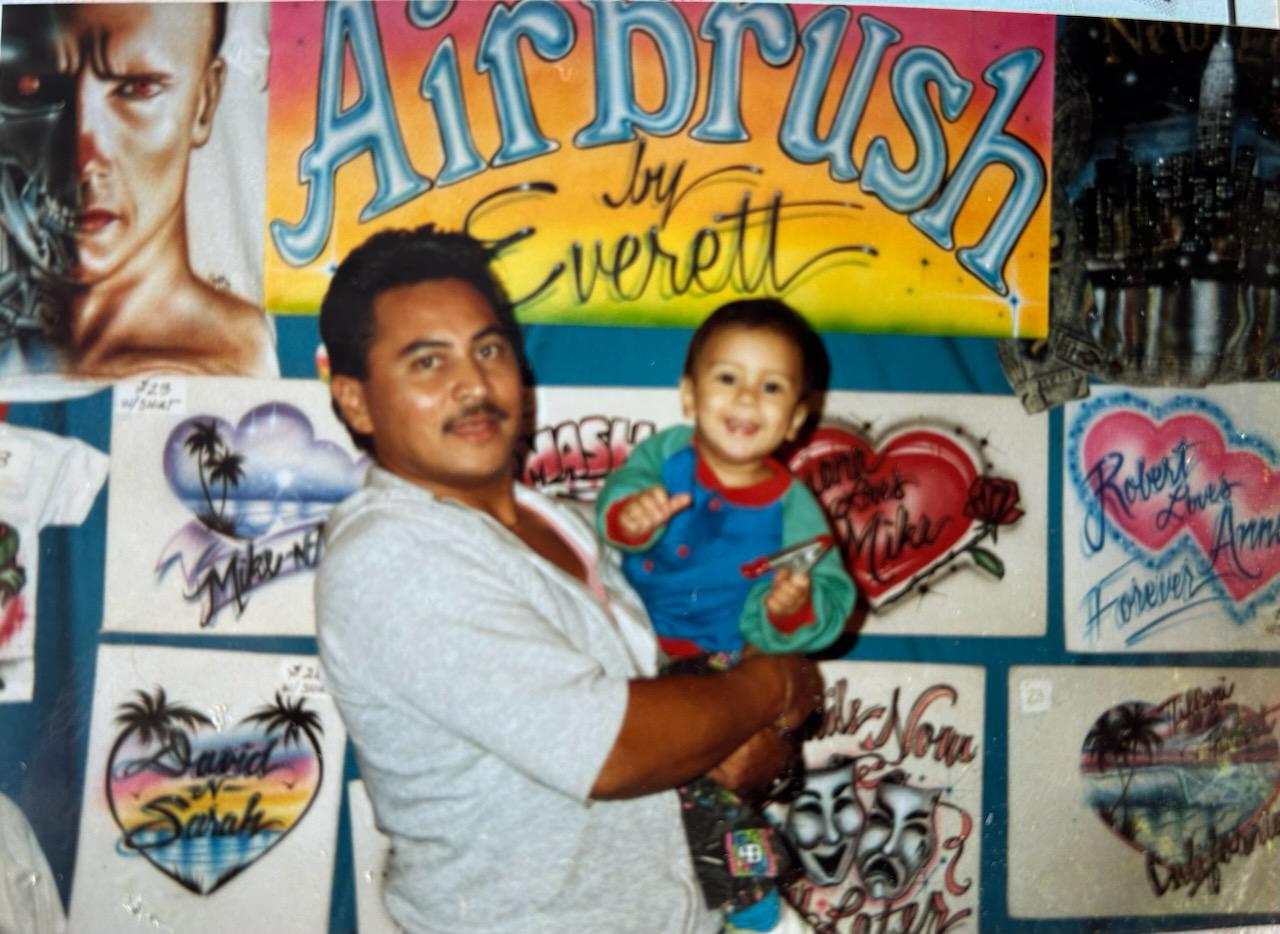

Regua has been airbrushing at various fairs, flea markets and venues around the Bay Area for 46 years. (Courtesy of Everett Regua)

Much of that has been lost in the modern Bay Area, says Regua. “They still do car shows and stuff but it’s not as popular as I recall back then. And the economy [has changed]. It takes a lot of money investing into a vehicle and getting a mural [painted on it]. It adds up and not as many people can afford that anymore like they used to.”

Though he still does traditional airbrushing (he did, after all, spray my son’s shirt), Regua has also adapted his business approach — he currently works corporate events and bar mitzvahs, now two of his largest sources of income, although he had never considered them until recently. According to Regua, those spaces increasingly hire airbrush artists to create designs for events and do on-the-spot airbrushing for attendees.

Despite — or perhaps because of — his 46 years of airbrushing experience, Regua shows no fatigue or signs of slowing down. He plans to remain at the flea market until its very last day, even as it confronts a precarious future. The San Jose Flea Market certainly feels like a husk of its former self. Having been aggressively reduced in size in order to build expensive condominiums, a BART station, and extensive retail properties around it, it’s no longer the thriving hub it was during my adolescence. For the time being, however, you can still find Regua posted up next to a rickety carousel, with dozens of his airbrushed Panama hats, white tees, and hoodies on display.

“Airbrushing is meditative,” he says. “I’m glad I’m able to keep doing it. People ask when I’ll retire. Why? I have a gift of art. I won’t retire until I can’t do it anymore.”

The art of hustle: “I was making hella money”

Shannon Anderson, better known as the popular tattoo artist Mo’Better, got his start as an airbrusher in the late 80s. Having moved to Hayward from the Midwest at a young age, he quickly realized there was a demand for airbrushed goods in the East Bay. He hasn’t stopped chasing the bag since. As a Mount Eden High School student, Anderson established himself by painting his own clothing for fun. His peers suddenly began requesting — and paying him — to do the same. He turned it into a business.

“When I started it was just at the height of being commercialized and popularized,” he recalls. “That was around 1990. By ‘91 [my friends and I] were killing it. I was averaging about $10,000 a month, just off airbrush. Everyone wanted street-style airbrushing back then. It was all over the music videos on MTV, on Martin and Fresh Prince, that was all part of the airbrush hype. So I marketed myself.”

Anderson began as a part-time airbrusher at Southland Mall in 1989, where he says he made “hella money” on weekdays after school, and up to $500 a day on weekends. As a beginning airbrush artist, he was regularly getting paid $2,000 a week — hella money, indeed, for a teenager in the 90s. He went on to save up enough funds to open his own fully-dedicated airbrush shop at Bayfair Mall in San Leandro. At the time Bayfair was a hub for East Bay youth, as the mall was (and still is) linked to a major BART transfer station and AC Transit bus terminal on a line that runs through Oakland and into San Francisco. Long before social media, malls provided all the dopamine rush and instant gratification that one could want. Besides himself, he remembers the late Dream TDK in Richmond’s Hilltop Mall as the most in-demand airbrusher in the East Bay.

His notoriety reached clients like Master P, one of the most influential rappers of the 90s and early aughts, who originally launched his independent record label No Limit Records as No Limits Records & Tapes, a record shop on San Pablo Avenue in Richmond, before moving back to his birthplace of New Orleans. Anderson redesigned Master P’s No Limit Records logo back then — among the most iconic Southern rap monikers of all time.

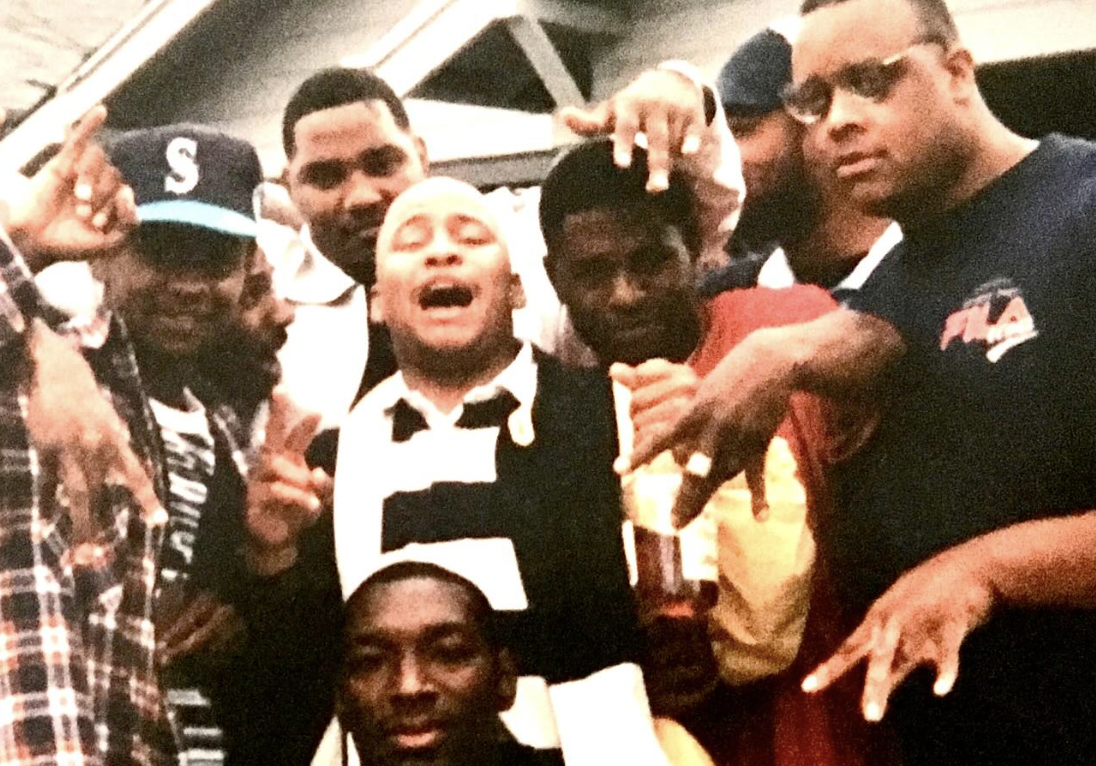

Shannon "Mo'Better" Anderson went from being one of the Bay Area's premier airbrush artists in the 90s to becoming a renowned tattooist. (Courtesy of Shannon Anderson)

When asked what made his East Bay airbrushing unique, Anderson recalls his days of selling “turf shirts” out of the trunk of his car. He drove around East Oakland delivering custom shirts that neighborhood high rollers would order and purchase from him in advance. Anderson, who lived in the area, would incorporate specific details familiar only to those from specific communities: a particular street intersection, a certain car parked on the corner, a notable element from a public park.

Around 1996, Anderson moved away from airbrushing and began to pursue tattooing. He’s now regionally renowned as the owner of Inkestry, a tattoo shop in the East Bay, with waits of up to two years to get tatted by Anderson himself. But he credits airbrushing as his entry point into a lifetime of artmaking.

Body painting, motorcycles and Formula race cars

Perhaps no one can tell you about how rugged and game-laced Oakland is better than Deandre “Airballin” Drake, who was raised in East Oakland’s Murder Dubs neighborhood during the 1980s. Airbrushing provided a necessary outlet — and economic pathway — at a crucial time in his life.

“I grew up in the dope era: cocaine, crack. I was part of that,” he says. “I was locked up for the entire 90s. I didn’t see anything; I missed that entire decade [in prison]. But when I came home in the 2000s, my first experience was seeing [a future mentor named Daryl] with an airbrush. I was impressed. Somewhere in me deep down, I always loved art and wanted to be an artist.”

(L) Deandre "Airballin" Drake grew up in East Oakland's "Murder Dubbs" neighborhood. He was incarcerated and taught himself how to draw in prison. (R) As an artist, Airballin specializes in painting motorcycles, race cars, custom pieces, and human bodies. (Courtesy of Deandre Drake)

While incarcerated, Airballin taught himself how to illustrate, and though relatively late to the airbrush game in 2004, he quickly became a top airbrusher in Oakland. After pursuing a mentorship with Daryl — who he praises as a lifeline and key influence for many airbrushers in those years, and who is now a tattoo artist at Oakland Ink — Airballin took off. He started out by opening a shop known as The Ave. Airballin’s first hire was an artist by the name of Prospect. Less than a year later, Prospect would become 510Airbrush, transforming into one the most sought-after airbrushers who personally supplied gear for rappers like Mistah F.A.B., E-40, and Keak Da Sneak. Prospect coined the phrase, “The Spray Area,” a nod to the Bay’s reputation for producing innovative graffiti writers and airbrushers. Together, the artists were responsible for much of the airbrush trends of yore, helping to expand the genre’s dimensions beyond regional trends.

Prospect, also known as 510Airbrush, was a key figure in Bay Area airbrushing during the hyphy movement. He regularly airbrushed clothing items for artists like Mistah F.A.B., E-40, Keak Da Sneak, and others. Examples of his work are pictured above. (Courtesy of Prospect)

Right as Oakland was entering a hyphy vortex, Airballin veered away from conventional airbrushing on clothing in favor of Formula race cars, motorcycles, and human bodies. He was hired by celebrities like NFL linebacker Joey Porter and rapper Snoop Dogg to paint Playboy Bunnies at Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Mansion. He has been commissioned to airbrush for Floyd Mayweather, Jay-Z, 50 Cent, and Nas. Airballin recalls how at his peak, social media hadn’t yet become what it is today — Facebook was just starting out, and TikTok was still an entire decade away — but he estimates that by MySpace-era metrics, he would be considered what is known as an influencer, and not just in the Bay.

“That took me all over the world: Amsterdam, New York, Miami. Everywhere. I even body painted at the Super Bowl,” he says. “I had clients that put me on private jets and flew me around to gigs. I once did a commercial for Fiat, and they had me paint 16 women for that. It was all life-changing.”

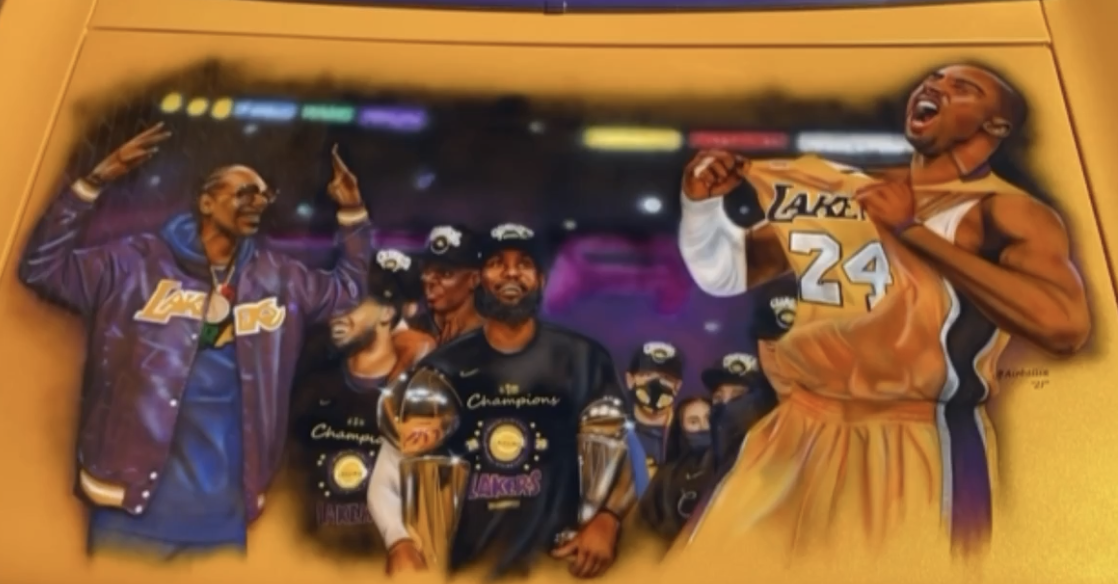

(L) A Haight & Ashbury-themed Volkswagen Beetle airbrushed by Airballin. (R) For Snoop Dogg's 50th birthday, the Long Beach rapper commissioned Airballin to airbrush his 1968 Mercury Cougar with a mural of himself, LeBron James, and Kobe Bryant. (Courtesy of Deandre Drake)

Airballin surmises how “graduating” from t-shirts and shoes and going into other lanes of airbrushing allowed him to gain recognition beyond a Northern California audience. Currently, he works as an art therapist in juvenile halls, and launched CREATE (Culturally Responsive Expressive Art Therapy and Engagement) for young men in the carceral system.

“From my perspective, I don’t think airbrushers all caught on,” he says. “Some couldn’t transition out of the shirts and shoes. There are very few of us left from that 2004 era.”

As for the current gen of local airbrushers, he lists J Norm Customs as a talented sprayer he mentored and who specializes in memorial tributes. There’s also Joel Rivas, an airbrusher in Vallejo who, according to Airballin, is setting the standard for the current era of airbrush artistry in the region. Rivas once sprayed Oscar Grant on a hoodie for Hollywood actor Michael B. Jordan after the star had filmed Fruitvale Station in 2013, and he also airbrushed a portrait of the Friday character Deebo on a plaid shirt as a gift for former San Francisco 49ers Pro Bowler Deebo Samuel. Though Airballin has never formally worked with Rivas, he keeps in touch with the younger artist online and says that Rivas has personally credited Airballin’s career as an inspiration.

“[Joel] is the dopest t-shirt artist in the Bay right now,” Airballin admits. “In all honesty, he’s better than me when I was doing t-shirts.”

It’s a reminder that the vibrancy and community of airbrushing endures, despite its diminishing size and visibility. While it has transformed and splashed its way onto new canvases over the years, it has also quietly remained exactly where it has always been as a colorful anachronism that is worth preserving for the next generation of Baydestrians. Looking at my son’s shirt is a reminder of that.