How Racket, Minneapolis’s Worker-Owned Newsroom, Is Covering Its Hometown Fascist Invasion

“This is the worst fucking time. But watching people’s response to ICE has been the most affirming thing in the world.”

“This is the worst fucking time. But watching people’s response to ICE has been the most affirming thing in the world.”

This week we've got strikes, slime, white rappers, psychics, goth nights, and more.

It’s time to stop waiting around for those in power to save us. We, the people, can get everyone’s basic needs met.

With Halloween and Día de los Muertos upon us, we dispatched a local writer to document her favorite cemetery in the Bay — which features a one-arm burial site.

In 2019, on Halloween, I showed up on Kitty Monahan’s doorstep unannounced, in full costume, to ask her about Richard "Bert" Bertram Barrett's left arm.

Earlier that afternoon, I had dressed as “zombie-apocalypse-survivor Rosie the Riveter” in preparation for a themed party my friend was throwing. But something else pulled at my attention. So with a couple of hours to spare before the event, I impulsively made my way to Hacienda Cemetery, an old resting ground tucked behind a creek that runs through the unincorporated neighborhood of New Almaden near South San Jose. The visit would be my third within that month.

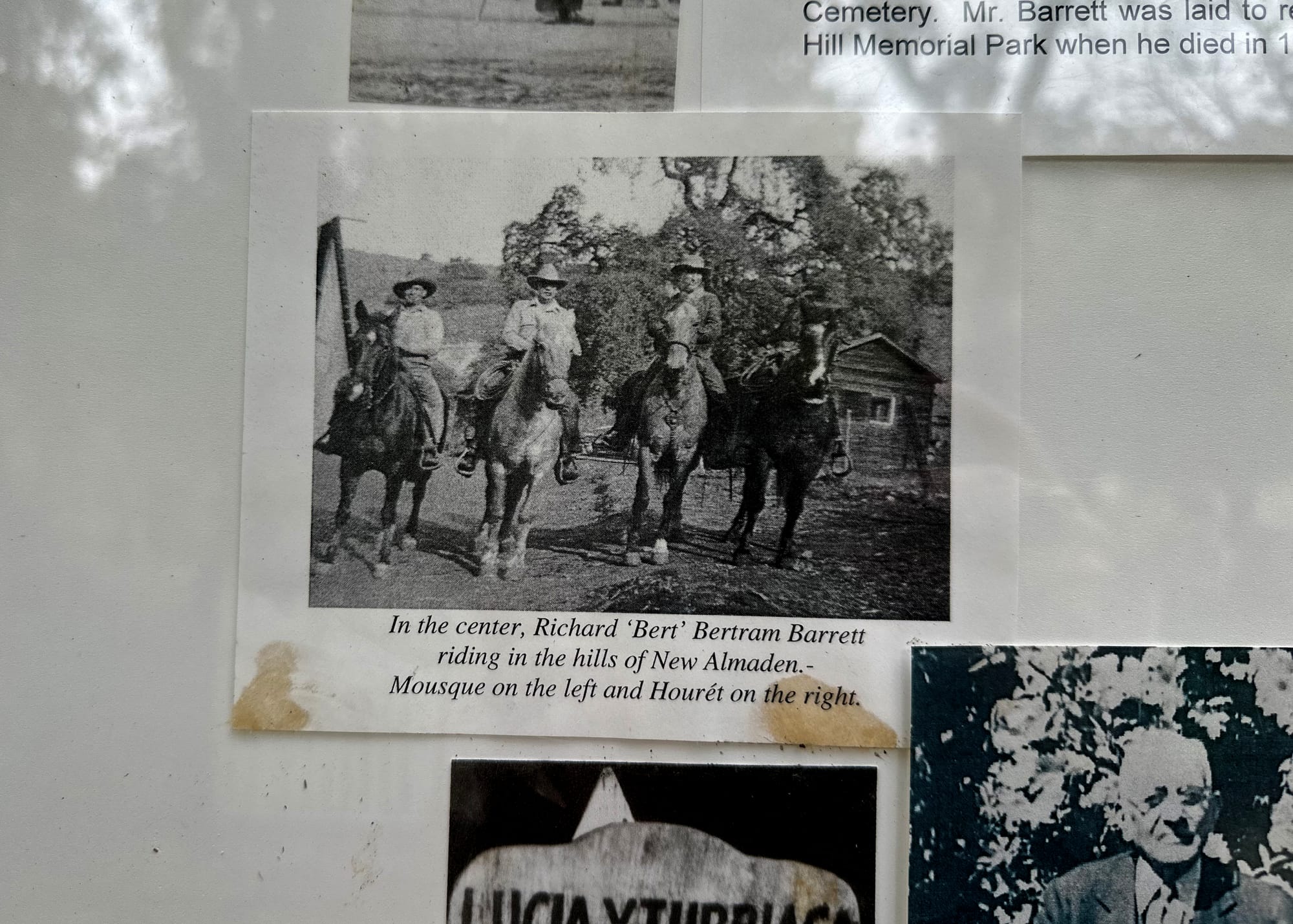

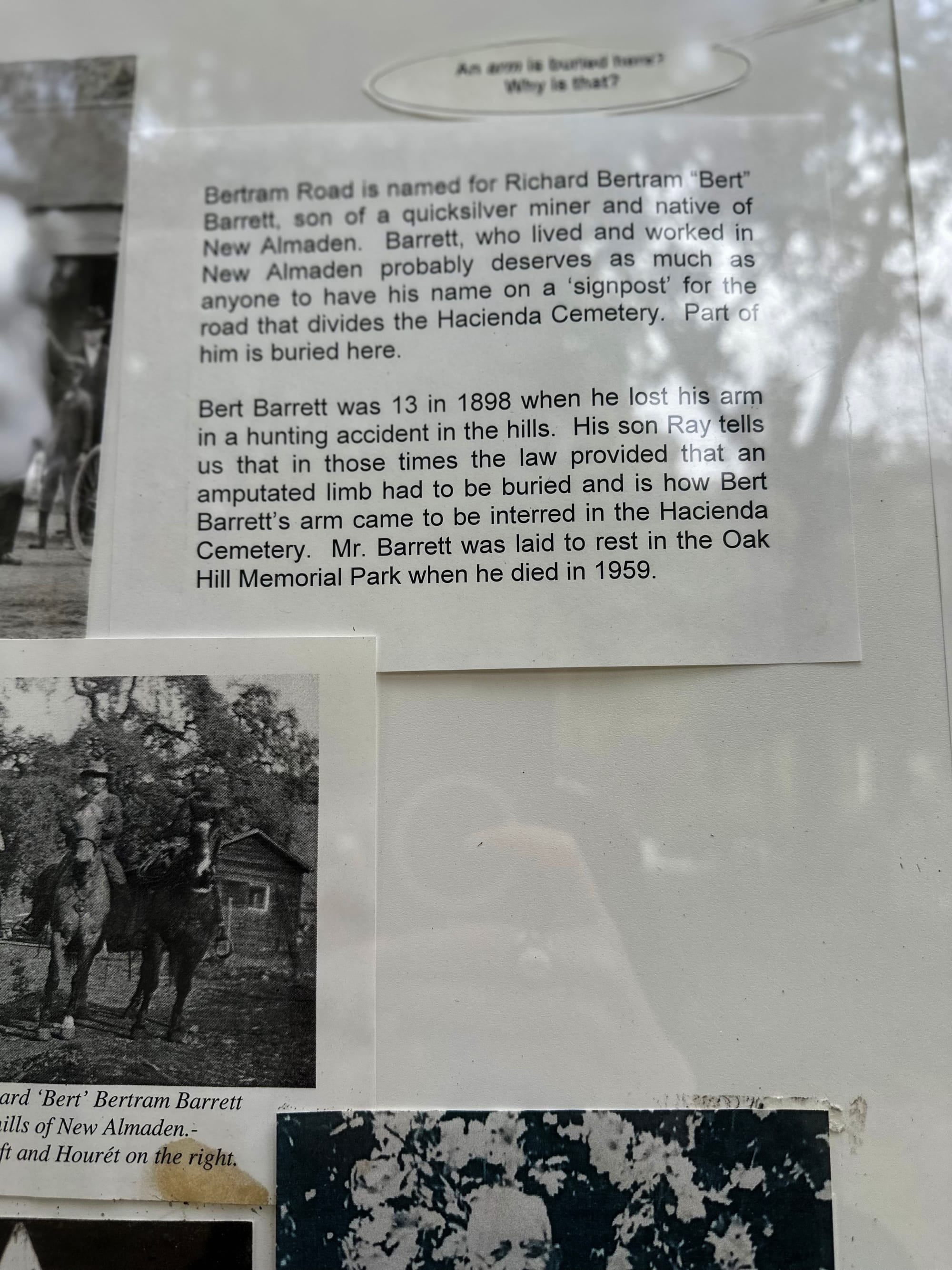

The cemetery is bisected by Bertram Road, and some of the dead lie beneath the narrow stretch of asphalt. The namesake of Bertram Road has one of the most famous epitaphs in greater San Jose history, belonging to a person who is likely one of the only who lies in two separate graves — miles apart. The inscription on the simple stone marker at Hacienda reads, “Richard Bertram ‘Bert’ Barrett. His arm lies here. 1898. May it rest in peace.”

According to local historian and Vice President of the California Pioneers of Santa Clara County Bill Foley, the date on the marker is wrong: It was in 1897 when a teenaged Bert went riding out to go hunting and fell off a fence he was seated on while holding a shotgun. The gun went off, sending a blast through his left arm at the mid-humerus and mangling it beyond repair. He lost the arm, but he lived. Though some sources will state his arm was buried in compliance with the law, Foley states the burial was more in accordance with the spiritual notion that Barrett and his arm would be reunited in the plane beyond. The headstone was added later.

I asked a local for more information on the barely decipherable tombstones — some of which are simple wooden boards weathered by the passing of nearly two centuries.

I was told Kitty would be thrilled to receive me to talk about New Almaden’s history. The local who had pointed me to her door (the old red house with the steep drive and two horses boarded in front) wasn’t wrong. So there I was, costumed and digging for answers.

(L) Amani Hamed dressed as a zombie-apocalypse-survivor Rosie the Riveter for Halloween 2019. (R) A poster of Rosie the Riveter. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/ J. Howard Miller for Westinghouse)

Kitty was a petite woman with white hair and glasses whose presence was like thunder. Holding what had to be the oldest dog to ever live, she ignored my appearance and invited me to sit at her kitchen table where she told me more about the boy who was partially buried at the little cemetery on a hill less than a quarter mile away.

The son of a quicksilver miner from Cornwall, Bert was a first-generation American. His name appears as a handwritten afterthought among his nine other siblings in the record of Cornish New Almaden miners and their progeny. After losing the arm, he grew up and lived to be 74 years old. He served as Chief of Sanitation in Santa Clara County and watched the valley transform from mines and orchards into a semiconductor boomtown aided by the massive gold rush that was still in full swing when he was a child. That boom was made possible by miners like his father, who dug out the mercury used to pull gold out of ore.

Bert passed away in 1959. He’s interred — well, the rest of him, anyway — at Oak Hill Cemetery in San Jose. He was cremated and his ashes are housed in an urn in a columbarium there.

Once, a local woman had told Kitty that she and other neighborhood children who knew him would run up to Barrett and untie his shoelaces. Before the advent of Velcro, Bert had learned to tie his shoes with just one hand. Local kids thought of this as a sort of magic trick.

“I guess he was good-natured about it,” Kitty said. “He would just bend over, tie his shoes, stand up and go, ‘Ta-da!’”

A photo of Barrett and his story are displayed at the entrance of Hacienda Cemetery. (Amani Hamed for COYOTE Media Collective)

Most kids in the neighborhood simply knew Barrett’s left arm as “The Arm” and, at night, would walk swiftly past the cemetery on their trick-or-treat rounds. As they passed, they would chuck a few pieces towards The Arm’s grave — a tradition that still continues to this day.

“If you don’t give him candy, The Arm will come out and chase you,” Kitty laughed. “Or, you know, that’s the legend.”

That day of my visit, however, I had only seen ofrendas laden with old photographs, burnt incense, fresh fruit, and cempasúchiles at other graves around the site. In honor of Día de los Muertos, and allegedly in honor of the miners (a mix of Indigenous and Mexican) buried at Hacienda Cemetery, the altars were spread with photographs and drawings of the departed, as well as family trees bedecked with oranges, cloves, and garlands of flowers. Veronica Cox, current president of the New Almaden Quicksilver County Park Association, says the altars are not permitted; nor are they built by families from the area or for miners interred there. But that’s another story for another time.

Bert Barrett’s ancestors had at one point done something similar, too. Though later conquered by the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex, the Cornish were Celts, bearing more cultural similarity to the Irish, Welsh, and Scottish. They celebrated the Celtic rite of Samhain, worshiped tricky gods who lived in the earth, and gave returning spirits of the dead offerings of food, dressing in costumes to confuse them.

On two different continents, separated by oceans, these disparate Indigenous peoples felt that the veil between the earthly plane and the realm of the dead grew thinner at specific times. Spirits became restless and needed appeasing. As the dead reached forward from the grave, the living reached back with gifts and glad tidings, flirting with the boundary between one world and the next. And here, outside the digital Mecca of San Jose, the descendants of Celts and Mexica peoples continue to collide, as the living erect altars with photos protected by plastic sheets, and children throw fun-sized Skittles packets at the grave of a boy’s severed arm.

Craig Rudy has lived on Bertram Road for 33 years and raised his children in the small house abutting the creek, just a few yards from the cemetery. He recalls his children hearing the legend of Bert Barrett’s arm: how it would come out and chase you if not given a sugary offering. Now, he says children are more likely to take candy from the cemetery than leave any, as the cemetery has become a stop on the Halloween trick-or-treat route.

“There used to be a haunted house right next door,” he says. “Halloween has always been a big thing around here.” Despite that, there weren’t that many other kids in the neighborhood when Rudy’s children were young.

Francesca Gordon grew up on Bertram Road at the same time as Rudy’s children, and recently moved back. She bought a house directly across from the cemetery.

“I think I first heard it from Mike Boulland,” Francesca says, referring to the tall tale of Bert’s arm clawing its way after children. She and other kids knew the adults were pulling their legs. “It was fun, but we knew it wasn’t real.”

She was one of very few youth in New Almaden back then, but as new families are discovering the charm of the little village — and people her age who grew up there move back — the area has seen a small boom in costumed revelers at Halloween.

“Now there are like 60 kids,” she says. “We all go trick-or-treating and go past the cemetery and then end at the community center. It’s nice that there are more kids now.”

Francesca herself has a toddler (who will dress as Elmo this year), and she’s also expecting twins. When I mention Kitty, she beams.

“Of course I knew Kitty — she was the unofficial mayor of New Almaden,” Francesca says. We spoke about the feel of the neighborhood and the importance of preserving things like an old cemetery rather than doing what seems to be the norm in greater San Jose: forgetting the past and its dead, tearing down history, and building over it all.

But in destroying our local relics, Kitty believed we ripped something crucial away from the future, from younger people like Francesca and her daughter, and left an unpaid debt to the dead.

“That was something Kitty had a problem with,” Francesca says. “She said San Jose wasn’t interested in preserving anything.”

Sitting in Kitty Monahan’s kitchen, I felt she understood how the dead have their hooks in me, just as much as they call to those who ritualistically assemble their ofrendas or give offerings to the bones of a child whose arm died before he did. It wasn’t just that we shared a fascination with history or with death, but that we both felt that the dead reach for us, and we couldn’t help but reach back.

Kitty Monahan passed away in that small, historic house less than three years after our encounter — in September of 2022. I only got to see her that once before the pandemic halted the world. She now lives, as the residents of Hacienda Cemetery do, in our memory.

Kitty devoted her later life to New Almaden’s history: specifically, to the history of the mine. “The people were the mine,” she told me that afternoon in her kitchen. The dead seemed to be all that mattered to her. She didn’t particularly care at all for the actual mine and its processes; nor for its facilitation of the gold rush.

Kitty was committed to active remembrance as a practice, which continuously honored the dead not simply because of what they had achieved or where they had come from, but because they had lived. This was the debt all the living owed to those who had gone on ahead of us, to those who two centuries ago had been buried in plain pine boxes and now sat beneath headstones rendered unreadable by the passage of time.

Whenever I visit the cemetery, where graves are huddled together as though the deceased are eternally congregating, I think of Kitty Monahan and the dead whose graves we walk over unknowingly.

She died in that tiny, red house, now owned by one of her nephews, but she was born in her family’s home just several streets away from me on Cleaves Avenue, in the Rose Garden district. A few blocks down is one of many San Jose streets named “Calaveras,” so named because waves of colonizers stumbled on the remains of Indigenous Muwekma Ohlone, people whose territory encompasses the entire Almaden Valley and the area below the Santa Cruz Mountains to the upper San Francisco Bay.

A cemetery is only as good as its recognition: a sovereignty conferred upon the dead by the living. The Muwekma Ohlone were initially disinterred by waves of Spanish colonizers and then American settlers who continued to not recognize the importance of those resting grounds. The Native people who painted themselves with red cinnabar ore, later clawed from the earth by the New Almaden mine to extract its mercury, still exist, though in smaller numbers. Their dead are everywhere in this valley, occasionally found when construction and urban redevelopment are forced to confront the old stewards of the land.

Today, Hacienda Cemetery’s sister resting grounds — Guadalupe Cemetery and Hidalgo Cemetery — are devoid of grave markers, but the dead may remain. Who builds altars with ofrendas for the dead we cannot confirm are beneath our feet? In many cases, it takes steadfast individuals and nebulous entities to preserve the scant history we have.

Right now, Hacienda Cemetery is owned by the California Pioneers of Santa Clara County, who — along with Boulland, who literally wrote the book on New Almaden history — are steadily rebuilding the “cribs,” or small fences around the graves. The property was deeded to the California Pioneers of Santa Clara County after a private citizen purchased it in the 1970s at a county sale of properties delinquent on taxes. Since then, it has been lovingly maintained by those who feel the yank of the dead like the tingling in a phantom limb.

This year, I returned to Kitty Monahan’s house after six years. I knew she was no longer there, though the house looked the exact same: complete with two horses out front and several chickens scratching in a yard monitored by an old tabby cat. The young man who turned down his music and answered the door — who it turns out was a friend of the family — smiled when I asked if he had ever met her.

“Yeah, she was a really sweet lady,” he said. “Just the nicest.”

Now, the inmates of Hacienda Cemetery and the ghosts of those who lived and worked at the grand white house below the graveyard are meshed in my mind with the dainty woman whose eyes twinkled behind large glasses when talking about the long dead of New Almaden.

She deserves the same remembrance she gave them: a remembrance not linked with accomplishment, shared lineage, or history’s cautionary tale, but one earned simply through the miracle of having lived, and in many cases died, in San Jose.

This story has been updated with additional information.

Amani Hamed is an award-winning journalist and freelance writer based in San Jose, California. She's won awards for her feature reporting, relishes investigative pieces, and enjoys film and media criticism.

View articles