How Racket, Minneapolis’s Worker-Owned Newsroom, Is Covering Its Hometown Fascist Invasion

“This is the worst fucking time. But watching people’s response to ICE has been the most affirming thing in the world.”

“This is the worst fucking time. But watching people’s response to ICE has been the most affirming thing in the world.”

This week we've got strikes, slime, white rappers, psychics, goth nights, and more.

It’s time to stop waiting around for those in power to save us. We, the people, can get everyone’s basic needs met.

Alternative newsweeklies launched careers, called out corruption, and made journalism fun. Can we bring that energy back?

When Brontez Purnell first moved from Alabama to Oakland in 2002, at age 19, his new residence provided a great crash course in Bay Area culture. A warehouse helmed by the punk band Erase Errata, it was packed with nearly two dozen other wayward youth.

But he didn’t feel he’d really arrived here until a couple of years later, when he got his first mention in a local newspaper: a San Francisco Bay Guardian write-up following a debauched club night in the city.

“We were outside some donut place, everybody in the scene was there, and I just remember getting naked and dancing in the middle of Polk Street,” says Purnell, now a critically acclaimed writer, musician, and performance artist. The next day, the Bay Guardian’s Marke Bieschke wrote about it. “I think he said ‘Illegal-minded skate punk Brontez Purnell was there, dancing naked,’” recalls Purnell with a laugh. “And I was like, ‘Oh, I’m in a real place! There’s nightlife, there’s gossip columns!’”

Of course, there was also a society column in the San Francisco Chronicle. But if you wanted to read a first-person scene report about naked dancing on Polk Street, you’d have to pick up the Bay Guardian. A free weekly published from 1966 to 2014, the paper focused on underground art, culture, and the LGBTQ community. It covered local politics with a progressive point of view, published adventurous narrative features, and its writers weren’t afraid to express opinions. In the space of a few pages, you could read a sex column, a profile of a local hip-hop crew, and the latest installment in a three-decade war with PG&E.

It was, in other words, a quintessential alternative weekly.

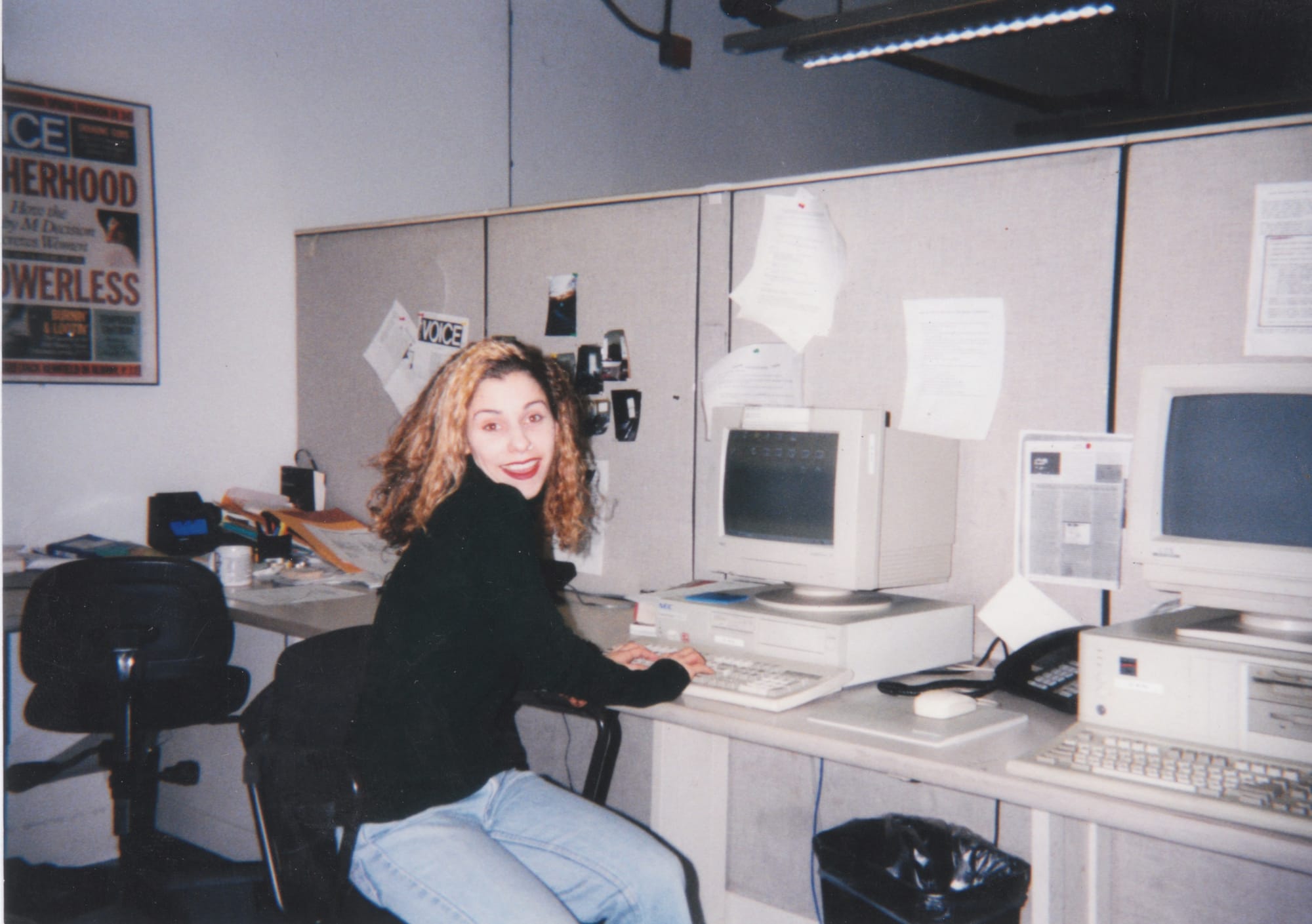

We here at COYOTE Media Collective intend to do “alt-weekly-style” journalism. But what does that mean? This question is both philosophical and literal, as we discovered a few weeks ago while tabling at Rainbow Grocery’s 50th anniversary party. There, upon hearing that “We’re trying to bring back alt-weekly-style journalism,” visitors responded with comments ranging from “THANK YOU” to “What’s an alt-weekly?”

So during COYOTE’s first week, we thought we’d try to define a few of our terms. What, exactly, were COYOTE co-founder Nuala Bishari and I missing two years ago, when we found ourselves huddled in former SF Weekly editor Astrid Kane’s kitchen at a party, reminiscing about alt-weeklies — and fantasizing about how fun it would be to just start our own?

Alternative weeklies are, broadly, free local newspapers that offer alternatives to mainstream media, in both topics and approach. While the Village Voice, founded in 1955, is widely considered the first alt-weekly, the Bay has a deep alt-media tradition of its own. Alongside the Bay Guardian, radical rags like the Berkeley Barb and Ramparts magazine chronicled the politics, art, and counterculture of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Weeklies thrived across the country well into the ‘90s and early aughts, with mastheads of several dozen people and papers that regularly topped 130 pages. Those papers broke news, took down corrupt politicians, and helped launch countless writers’ and artists’ careers. They were the class clowns of local media — sometimes bratty, but smarter than they looked.

These papers thrived, until they didn’t. The Bay Guardian was shut down abruptly in 2014, while its longtime competitor, SF Weekly, endured until 2021. (Full disclosure: I worked, for a time, at both.) Alt-weeklies do technically still exist in the Bay Area, albeit in diminished form. Many of them, including the once-formidable East Bay Express, have been hoovered under a publishing company called Weeklys, sharing limited editorial resources across ever-thinning page counts.

Suffice it to say, the alts’ glory days are over. Blame mismanagement, blame Craigslist swallowing the classifieds, blame a cascading series of buyouts and mergers that led to papers known for fierce independence being owned by various vultures in suits (you would be right on all counts). But the Bay Guardian and the Weekly did not disappear from news racks because people stopped wanting to read them.

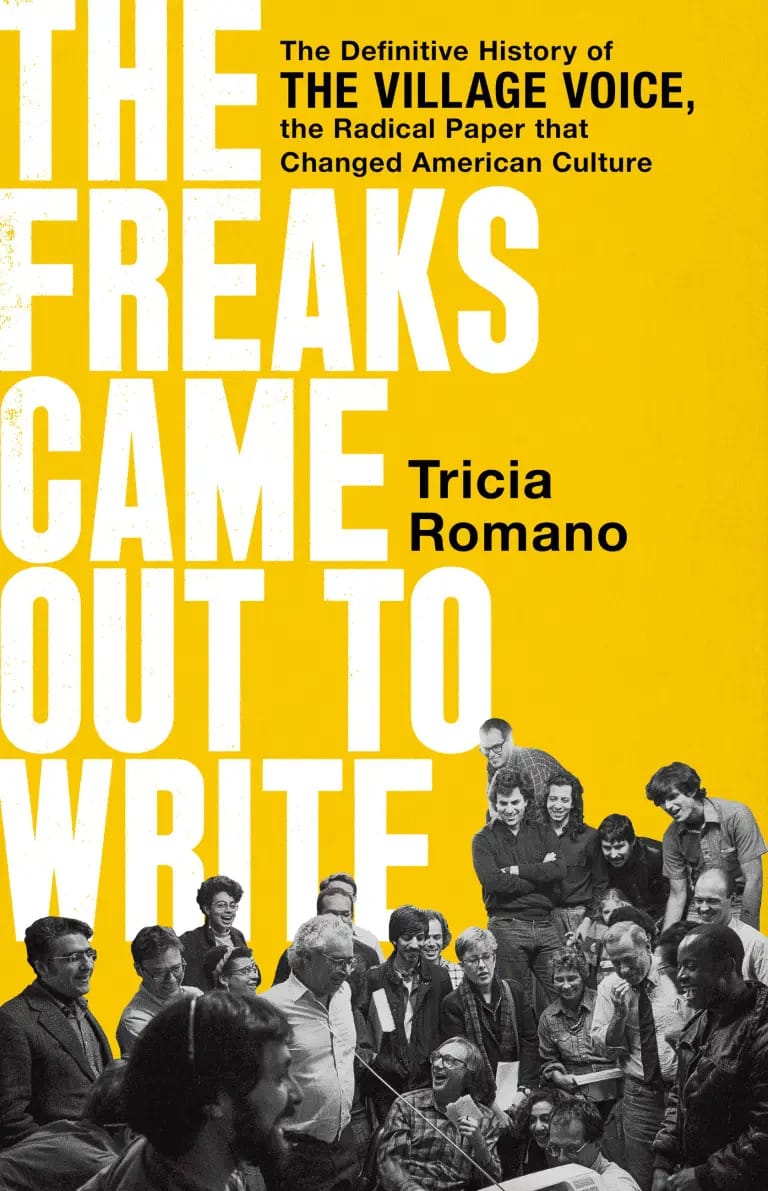

To be clear, alt-weeklies were far from perfect. They didn’t pay well, at least not by the time I got there. And — as I was reminded reading The Freaks Came Out to Write, Tricia Romano’s detailed oral history of the Village Voice — their boys-club culture could be toxic as hell. There was camaraderie in the weekly newsrooms I worked in, but the deep friendships I formed could also accurately be described as trauma bonding. Toward the end of SF Media Company’s ownership at the Weekly, meetings regularly devolved into screaming matches.

So how on earth do so many alt-weekly alumni still hold a torch for these papers?

Why, for so many of us, was it the best job we ever had?

In 1974, when Bruce Springsteen needed a new drummer, he placed an ad in the Village Voice, the only tri-state area publication that covered — and was religiously read by — up-and-coming artists. Max Weinberg, who showed up to audition, still drums for the E Street Band some 50 years later.

Back before the New York Times would deign to review an off-Broadway play or a rock band at a small club, the Village Voice — featuring titans of music criticism like Robert Christgau and Lester Bangs — set a new kind of standard. With culture journalism that assumed a baseline of curiosity and savviness from its readers, alt-weeklies insisted on outsider art as a given, as fundamental, as both the true heartbeat of a place and a central tenet of coverage for any outlet worth its newsprint.

For artists, that meant everything. “If you were a tiny band and you got a two-paragraph write-up in the Village Voice, you could put that in your bio sheet, and that was your calling card, you know? It meant legitimacy,” says Romano.

And for music fans trying to find the next cool thing, it was a bible. “It’s probably hard for people to even conceive of now. You can type a band into Spotify and get 15 more bands like that to listen to,” she says. “But back then, this was the speed of information, and how you got recommendations. It was curation.”

In the Bay Area, the arts were embedded in SF Weekly’s DNA: The paper grew out of a DIY affair called the San Francisco Music Calendar, first published by a group of musicians in 1981. Ann Powers, now NPR’s esteemed music critic, was one of the Weekly’s founding writers as it took shape, and she remembers the paper as a touchstone of the city’s cultural ecosystem, back when San Francisco was “this beautiful bohemia.”

“The art house cinema world was attached to the avant garde theater world, which was attached to the club scene, which was attached to the art galleries, and you had them all connecting in places like Intersection for the Arts, which had everything from poetry readings to political activism. Everything was just happening,” recalls Powers, who moved from the Weekly to the Village Voice to the New York Times. “And to navigate through that, the alternative weeklies were your map.”

Powers remembers going to shows most nights, then working into the early morning at the Weekly’s old office on Bryant Street, putting together the week’s calendar listings. “We’d be there until we could hear the garbage trucks, which is how you’d know it was like 5 in the morning,” says the writer. “But those listings were so important, because that’s what told you how to live your life in the city as a person who loved the arts.”

For Marke Bieschke, who joined the Bay Guardian staff as a columnist in 2005 and was executive editor at the time of its closure in 2014, the responsibility of covering the Bay’s artistic subcultures felt personal. As a teen in Detroit, he had devoured the Detroit Metro Times, thrilled by the world it depicted.

“It introduced me to alternative culture,” recalls Bieschke, now the co-founder and publisher of the Bay Guardian’s online descendant, 48 Hills. “It was so exciting to read about things that were speaking directly to my experience: punk rock or hip-hop or queer things, drag, underground nightlife… written by young people, diverse voices. It gave me a gateway to this centuries-long tradition of journalism that’s beneath the surface and against the mainstream.”

At the Guardian, Bieschke saw how the paper itself became part of the scene as well. “It was an artifact, an art object,” he says. “Seeing these great covers and photographs in stands throughout the city was almost like an art show every week — these beautiful, curated things to look at on every corner, this free aesthetic object that described the city.”

The physical paper is part of Purnell’s memories too. When he worked at the Castro diner Sparky’s (RIP, 1985–2016), the weekly was just another character at the notorious 24-hour eatery.

“There were like 10 clubs that all let out at the same time, and everyone convened at Sparky’s, so it was like a nightclub unto itself. This was before everyone was Uber-Eating shit,” Purnell clarifies. “And there would always be stacks of Guardians there, so that’s what people would be looking at. That’s how it was. People communicated via fucking parchment.”

One reason it’s tricky to explain how vital alt-weeklies were to the journalism ecosystem is that so much of the rest of that landscape has disintegrated. To people under 30, saying “working at an alt-weekly was a stepping stone to writing for a big magazine” likely lands a little like explaining that Woolworth’s was a great place to buy a rotary phone.

So let’s just say that alt-weekly newsrooms were a kind of journalism boot camp: in exchange for a paltry salary and increasingly inhuman blog-production quotas, you grew by necessity into a dexterous, deeply sourced generalist with a sharp, specific voice. You became adept at finding and turning out 3000-word cover stories, pithy columns, breaking news, and arts criticism — often all in one week. If you were lucky, you also got a mentor for life.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, writing in The Atlantic after New York Times editor David Carr died, spoke reverently of the boot camp that was the Washington City Paper, where Carr edited him in the 1990s.

“…you could not work for City Paper without learning how to walk the streets of D.C., approach people you did not previously know and barrage them with intimate questions. This is an essential skill for any journalist — but it is also one of the hardest things to do. … David Carr convinced me that, through the constant and forceful application of principle, a young hopper, a fuck-up, a knucklehead, could bring the heavens, the vast heavens, to their knees. The principle was violent and incessant curiosity represented in the craft of narrative argument.”

It is no surprise that this environment shaped many of America’s best contemporary writers: Hilton Als, now at the New Yorker; Manohla Dargis, at the New York Times; Colson Whitehead, a two-time Pulitzer-winning novelist.

Still, when I reflect on alt-weeklies, the writers I think about most aren’t those who went on to the big leagues. They’re people like John Graham, SF Weekly’s longtime clubs and calendar editor, and Willamette Week’s music editor before that. A skilled critic and an eternal punk kid, John had a sharp wit, discerning taste, and zero tolerance for bullshit. Where I had a hard time keeping a straight face in meetings with corporate stooges, John never bothered to try.

When he died in April, I thought about pitching an obituary around. But the only place that would have made sense — the only newsroom, to my mind, where he really made sense — was an alt-weekly.

Romano’s main goal, when she first began researching her book, was to capture memories from the Voice’s eldest writers before they were lost to time. Quotes from hundreds of excellent, shit talk-filled interviews are organized chronologically; otherwise Romano imposes little structure.

But certain questions snake their way through the text. Such as: Is there a need for a paper like the Voice anymore? The book illustrates how alt-weeklies were so influential, they changed mainstream journalism — including the publications to which they were an alternative.

Sia Michel, for example, the deputy culture editor at the New York Times, is a Voice alum. Unsurprisingly, “their arts coverage is much more like the Village Voice now than it was 30 years ago,” says Romano.

It’s true: “Alt-weekly-style journalism” can now be found throughout the media landscape. That’s in part because alt-weekly alumni are everywhere, cosplaying as straightlaced journalists at an outlet near you. Former SF Weekly staff writer Joe Eskenazi, for one, is the managing editor at Mission Local, where he anchors the site with a Weekly-esque blend of humor, deeply sourced investigative reporting, and something the alts were great at: context.

So it’s telling that, when SF Weekly finally shut down, Eskenazi published the best elegy I saw.

“...we are all poorer for not having a functional alt-weekly in town. And not merely because more professional journalists and more credible outlets is better than fewer. But because alt-weeklies, specifically, best understood how a city worked — or did not work. … Reporters elsewhere often share the real story with their colleagues over a drink after work. At an alt-weekly, the real story was the story in the paper.”

Occasionally, you will hear alt-weeklies described as a two-way mode of communication, as “mirrors” for their cities. Which raises the question, what does it mean if both of your city’s alt-weeklies die entirely? (Seems bad!)

Indeed, the Bay Area’s population is older than it used to be. It also isn’t news that artists can scarcely afford to live here anymore. The weeklies were not exclusively for young people, nor artists, but they did require a certain level of interest in, well, going out.

“Alternative weeklies, in their classic era, were connected to this whole ecosystem,” says Powers. “To have a healthy alternative weekly, you have to have people who can afford to live in the city, who do the things the weekly supports and is supported by. To go to the bars, go to the shows, buy the futons, read the personals … the weeklies facilitated actual human interaction.”

Bieschke believes there are plenty of people still here, of all ages, who want to know about underground art and music, even if they’re not partying until dawn. But you might not get that impression from mainstream news sources. Alt media outlets are crucial, he says, because they push back against narratives that preserve the status quo, or booster-ish culture coverage that prioritizes commercially successful work.

“I don’t want art to be harnessed to fill commercial realtors’ pockets,” says Bieschke, of arts-focused initiatives to “revive” downtown San Francisco and the media coverage they’ve received. “And who are these people arbitrating the arts? Why is it only four of them, and they’re all white guys? I don’t want Burning Man art littering Golden Gate Park. We can do better.”

He’s enthusiastic about COYOTE in part, he says, because the Bay Area needs more voices in the conversation.

“One of the great lessons of the post-alternative weekly world is that we didn’t welcome enough different voices … that’s something people really appreciate [at 48 Hills],” he says, of the site’s contributors. “[Readers] see the care, you know? They don't even have to read the 2000-word article on dancers activating the cornices of City Hall in an attempt to recognize the genocide against the Ohlone people, but they love that someone cares about that story. Those stories are there for history, and they’re there for people who want them, and they’re there for people to look at and go, ‘Well, at least somebody’s [covering] it.’”

my most Gen X coded belief is that cities and the culture at large suffer profoundly for the near-complete death of alt-weeklies

— Sam Adams (@samadams.bsky.social) May 27, 2025 at 2:54 PM

[image or embed]

Romano has thought a lot about what the alt-weeklies could do in their heyday, what they did, and what hasn’t been replicated elsewhere. There’s a line she returns to, near the end of her book, from Joe Levy, a former music editor at the Village Voice:

“...without the Voice, there is one less advocate for the rights of sex workers, or the rights of immigrants. One less outlet hearing those voices. One less place to be noticed as an aspiring playwright, musician, choreographer … The Voice is a place that took things seriously — small things, developing things, emerging things — that other places didn’t. That’s what it always did.”

Emerging things, after all, have a way of turning into bigger things. Powerful things. History-shaping things. Read anything by Wayne Barrett in the Voice from the late ‘70s, and you’ll find that “the Village Voice was investigating Donald Trump in 1979, and not kissing his ass, which is what all of the other papers were doing,” as Romano notes. Then, as now, the big mainstream outlets were concerned with maintaining access.

But “Wayne dug right into it. And if you [read those stories], you saw who Donald Trump was, even then — through his deals, and how he made those deals, and not, you know, his disarming personality or whatever, and his beautiful wives,” she says.

“Only an alt-weekly is going to do that. Right?”

Emma Silvers is a San Francisco journalist with 15+ years of experience covering the people and policies shaping arts and culture in the Bay. She grew up in Albany and lives in the Mission.

View articles